China’s grand European plan, along with Italy announcing its formal participation in the Belt and Road Initiative, means that China is on everyone’s lips. Since 2013, China has acquired shares in 14 European ports (not including ones with MoU agreements). While there is on-going debate regarding the strategic aim behind these acquisitions, this article looks one step further and asks whether Chinese trade flows are following China's acquisition pattern.

Since 2013, China has acquired shares in 14 ports in Europe (not including ones with MoU agreements). COSCO Shipping Ports and China Merchants Port, two state-owned companies, are the main investors in these ventures. China Merchants Port, a subsidiary of China Merchants Group acquired shares in ports in France (4), Belgium (1), Greece (1) and Malta (1), by purchasing 49% of the company Terminal Link (CMA CGM Group), in 2013. COSCO has invested in 8 ports in Europe, out of which five are located on the Mediterranean Sea and three on the North Sea.

With the exception of Euromax Rotterdam and Antwerp Gateway, China has mainly acquired terminals in medium-sized ports, aiming to turn them into major gateways. The most famous case is Piraeus in Greece, whose throughput (TEU) ranked 7th in Europe by 2017. While there are on-going debates about China's strategic aim regarding these acquisitions, this article digs deeper and asks the question: is the Chinese trade flow following China's acquisition pattern? This question is relevant because building the global shipping network should optimize China’s supply chain and boost international trade.

Mixed results

The quarterly volume data of shipment from/to China in these ports shows mixed results. While there is an increase in the total volume of goods shipped to/from China, there is a significant increase of inward flow from China and a fluctuated and slightly decreasing outward flow to China (Figure 1). This mirrors the China-EU trade pattern. The increase mainly comes from three ports: Piraeus, Antwerp, and Rotterdam. But for some of the ports, acquired more recently, we may need more time to evaluate the impact and overall exchanges. In Zeebrugge, where COSCO acquired 85% of APM Terminals in September 2017, there was a significant increase in throughput during the second and third quarters of 2018. However, this growth is mainly attributable to trade with Russia and Brazil. China is only the third largest contributor to this trend.

Figure 1 : The quarterly data of gross weight of goods (thousands of tonnages) inward/outward from/to China (2010-2018), Data source: Eurostat

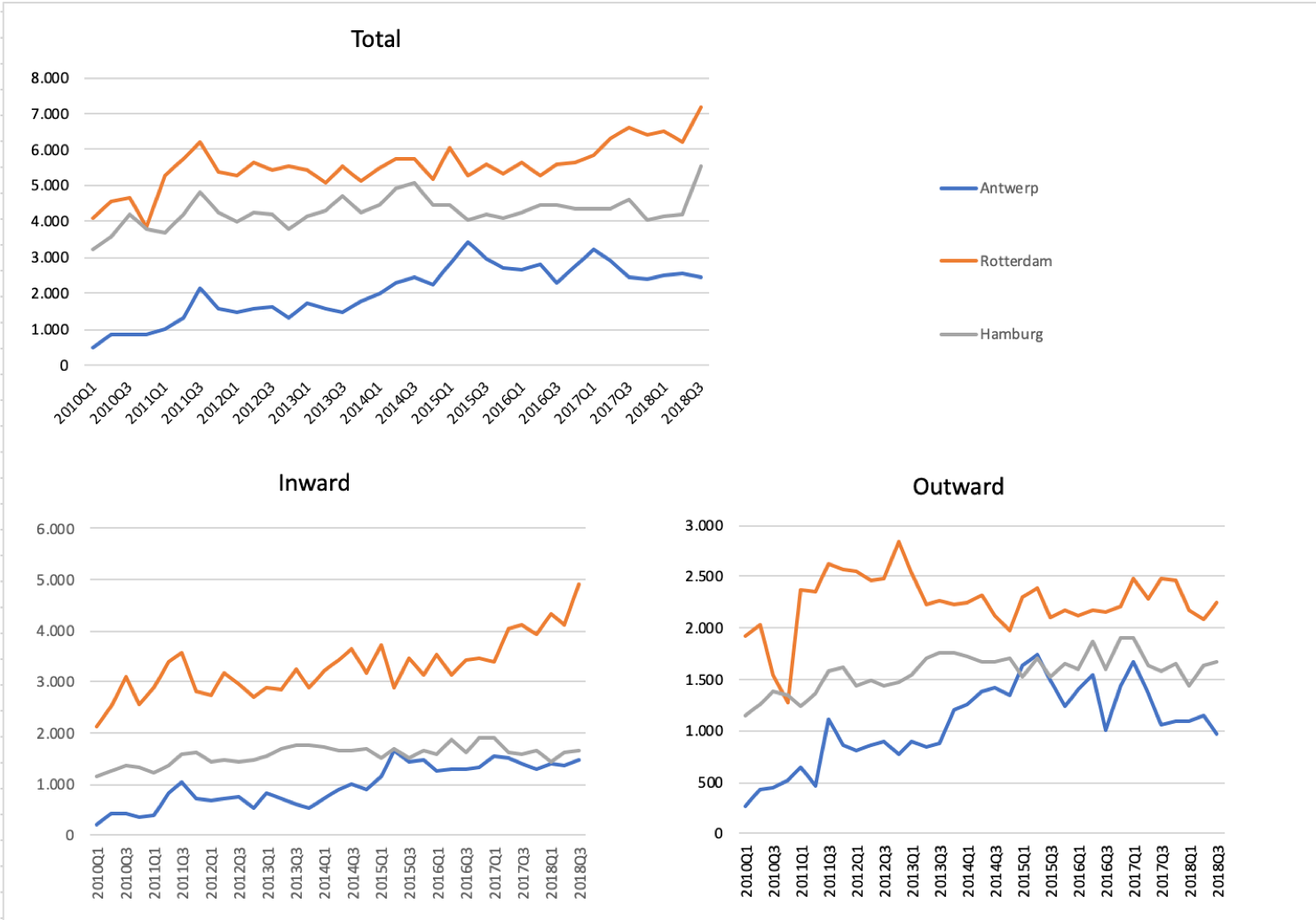

China has acquired terminals in Rotterdam and Antwerp, 2 of the top 3 ports in Europe. These same two ports have had a more important growth of their exchanges with China than Hamburg (figure 2), the third port in this top three, despite all three being connected to great railway shipping networks. Additionally, since 2013, the volume of goods shipped to Europe from China via Rotterdam has increased significantly. In comparison, the volume of goods going to/from China transiting via Hamburg has stayed about the same.

Figure 2 : Quarterly data of the top 3 European ports (thousands of tonnages) inward/outward from/to China (2010-2018), Data source: Eurostat

Figure 2 : Quarterly data of the top 3 European ports (thousands of tonnages) inward/outward from/to China (2010-2018), Data source: Eurostat

Findings suggest that shipments to and from China remain concentrated in the top 3 ports in Europe, rather than flowing to other Chinese backed terminals. Piraeus, whose shipping volumes have increased tremendously, seems to be the only successful Chinese investment case in Europe so far. Can China replicate its success in other ports as it aims to, for instance, in Zeebrugge? Will Chinese shipments flow to other ports in the mid to long term? The following three aspects may help us to get a better idea.

- Firstly, the current Chinese economic slowdown creates uncertainty for future port development, and more specifically, it begs the question of whether Chinese trade performances can sustain the rapid expansion of the shipping network. In the last two years, China has slowed down its acquisition of ports in Europe, the peak time being 2016 and 2017. It is possible for this slowdown to last a while.

- Secondly, the degree of cooperation between the Chinese local teams will also affect terminal performance. Looking at Zeebrugge for example, APM Terminals (now CSP Terminals) is currently COSCO’s largest equity participation in Europe after Piraeus. Following COSCO’s investment, Shanghai Lingang Group invested €85 million to build a distribution park in the inner port in Zeebrugge. It will be an opportunity and challenge for Chinese investors, in terms of communication, management style and regulation compliance, to ensure a long-term consistent development strategy.

- Third, on a macro level, success will depend on how China prioritizes the strategic significance of these ports, both economically and politically. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is driven by a strong political motivation. When one project meets both China’s political interest – i.e. norm diffusion and national image – and economic interests, it becomes a priority. Piraeus meets both requirements. Economically, it serves as a critical connecting point for the BRI since land and sea routes meet. Politically, as the flagship port project in Europe, it serves as a sample of successful infrastructure cooperation between China and Europe. Trieste, the recent rising star, also meets both requirements, even though no Chinese SOE has acquired shares in the port so far. Politically, Trieste can set a perfect example of collaboration with Italy, the first G7 member to join the BRI. Economically, Trieste allows China to extend the Ambari-Piraeus Mediterranean shipping network to the west, and it provides a direct access to the European railway network.

It seems still too early to draw any conclusion. Port development is a long-term process: the investment’s impact and the role of the overall economic situation can only truly be assessed a few years out. After COSCO’s acquisition of a 35-year franchise for Piraeus in 2008, Greece experienced the serious economic crisis. The port only started growing after 2010.

Overall, China’s port acquisition strategy fits within its broader multi-modal shipping network development plan, and more specifically with its project to create a Eurasian water-railway network. Meantime, the EU is also developing its multi-modal shipping network: the Trans-European Transport Network or TEN-T. China has repeatedly shown interest in the cooperation between Belt and Road Initiative and TEN-T. But the newly passed EU framework for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) screening, listing the TEN-T in the strategic field for these screenings, indicates the EU's concern regarding Chinese overseas infrastructure investment. Will there be competition or cooperation between TEN-T and BRI, particularly in the Mediterranean region, and also in Central and Eastern Europe? We will address this topic next time.

Ganyi Zhang

PhD in Political Science

Our latest articles

-

Subscriber 3 min 24/02/2026Lire l'article -

Hapag-Lloyd - Zim: a shipping deal with geostrategic implications

Lire l'article -

European road freight: the spot market is stalling

Lire l'article