When we talk about the circular economy in the supply chain, we generally think about optimizing logistic circuits and "reverse logistics". But road transport can also take part in the more general move to a circular economy. In many ways, it is already involved…sometimes without knowing how to best take advantage of the fact.

New techniques, which will enable the transport sector to make its own the principles of the circular economy, are starting to make their appearance.

1- What are we talking about?

When he was invited to close the congress on the circular economy organized by GS1 on August 31, French explorer Jean-Louis Etienne, a doctor in medicine and a member of the French Academy of Technology, put forward a convincing comparison between nature and the economy. He argued that nature divides roughly into three categories, each of which is both a supplier and client of the two others: the producers (e.g. plants), the consumers (e.g. herbivorous and carnivorous animals) and the recyclers (e.g. earth worms and woodlice).

Taking inspiration from this mode of organisation, he said, would mean substituting the linear "produce, consume and throw-away" model by a circular "produce, consume and recycle" model. The optimal configuration would be that the rubbish of those on one side would become the resources of those on the other. It is simple and concrete.

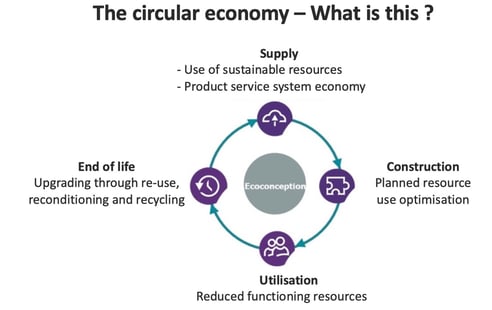

The diagram below, which comes from an article in a blog by consulting company Wavestone explains the "eco-conception" behind the circular economy process.

Several major principles need to be respected:

- Preserve natural capital by controlling finite resources and balancing out renewable energy reserves;

- Optimize resource yields by making maximum use of products and materials at all times;

- Reinforce system efficiency by detecting and eliminating negative external factors.

2- How does it apply to road transport?

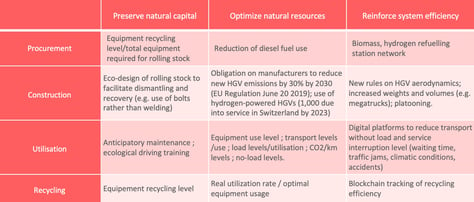

The circular economy can be applied to road transport on the basis of the principles and examples given in the schema below:

Source : Upply

The specifics of road transport can be resumed in three points:

- Diesel fuel is demonized, while the search goes on for alternative forms of energy ranging from other carbon fossil fuels to hydrogen batteries;

- Great technological progress is being made in the mobility sector, auguring a marked increase in operating performances;

- European legislation acts as a strong driving force for reducing gases harmful to man and the climate. The European Union has set itself the target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 80-95% by 2050 as compared to 1990 levels. The aim is to respect the terms of the Paris Agreement, which aims to keep global warming this century well under 2°C as compared to pre-industrial levels.

3- Resource optimization

- Reducing heavy goods vehicle (HGV) emissions

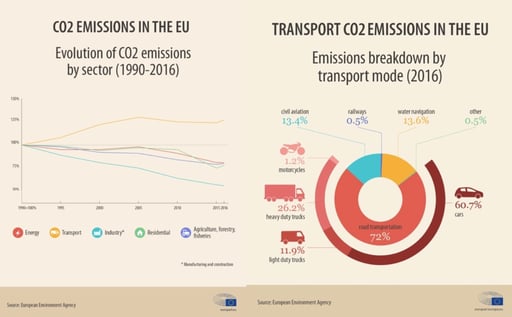

The first diagram below shows that all sectors except transport have started to reduce their emissions. In 2016, the transport sector produced 20% more emissions than in 1990. The second table shows that privately owned vehicles are the main source of CO² emissions, accounting for more than 60% of all transport sector emissions. Road freight transport comes second, accounting for more than 25% of the sector's emissions and 6% of total European Union emissions.

Despite some improvements in engine fuel consumption, emissions are continuing to increase as traffic grows and, particularly, distances covered (see our article on the evolution of road transport over the last 10 years).

The European Union has therefore taken a series of measures aimed at accelerating progress in road transport.

European Union regulation 2019/1242 of June 20 2019 obliges vehicle manufacturers to reduce the CO² emissions of new heavy goods vehicles by 15% by 2025 and by 30% by 2030, generating estimated fuel cost savings of €5,000 and €11,000 per vehicle per year respectively. The objectives in the regulation are expressed in percentage emission reductions compared to the EU average over the July 1 2019-June 30 2020 reference period.

The regulation will apply first to heavy goods vehicles, which account for two thirds of CO² emissions. But, on the basis of a report to be presented by the European Commission to the European Parliament and the European Council by December 31 2022 at the latest, CO emission reduction targets are due to be proposed for other types of heavy utility vehicles, such as trailers, buses and coaches and special-purpose vehicles.

To measure CO² emissions and fuel consumption, vehicle manufacturers will have to use VECTO, a simulation tool developed by the European Union. Rewards are planned for pro-active operators, as are financial support measures.

- Digitalisation to share resources and improve efficiency

The development of digitalisation in road freight transport should bring a whole range of options for optimizing transport performance and improving the way that equipment is used. Among other things, this means that:

- the management of transport supply and demand via large platforms will reduce the number of kilometers covered without load;

- real-time connection to the supply chain and artificial intelligence will allow loading and unloading schedules to be reorganized according to circumstance, ensuring that capacity is better used;

- permanent control via the Internet of Things and geolocation will reduce efficiency losses caused by under-loading and excessive energy consumption, as well as providing greater security for people and goods.

- Clean fuels and multi-modality

The current trend is to give preference to clean fuels for short distances and to multi-modal transport for long distances:

- Transporters like Jacky Perrenot for Cdiscount, offer electric transport services.

- Railway stations like Duisburg in Germany and Antwerp in Belgium have become real European multi-modal hubs, breaching the undisputed domination of road transport for long distances.

But efforts are also being made to develop multi-modal transport for short distances and the use of clean energy for long distances:

- Access to rivers and their links with road networks serving major towns and cities is the combination which Green Switch Meridian plans to use to develop its business in France in such centres as Paris, Strasbourg and Bordeaux.

- Hydrogen-powered trucks (Tesla, Nikola, Toyota and Hyundai) with zero carbon emissions offer exciting prospects thanks to their fuel autonomy, which is comparable to that of diesel.

- Opting for short circuits to reduce distance

The "local economy" theory, involving, for example, the consumption of local agricultural products, is very much in fashion. We are seeing the emergence of new consumer habits, which as they develop, could help to reduce the CO² emissions generated by long-distance transport, which accounts for 50% of ton-kilometers in Europe.

The creation of local recycling circuits can also help to reduce transport distances.

- Recycling and more recycling!

Better coordination between flows of incoming materials and outgoing products and waste is essential for the recovery cycle. In flat glass transport, for example, ways are being sought to recover the cullet left over from glass-cutting by enabling it to be returned by the same rolling stock which brought the glass in the first place. Given that glass is totally recyclable, there is no waste.

Dismantling transport equipment which is no longer used, reusing spare parts and recycling the materials of which they are made are becoming increasingly a necessity. Mercedes Benz Trucks and its partner Autogreen have already launched a service of this sort in the UK.

4- Resistance and obstacles

Efforts to move road transport from a linear operating model to a circular one will certainly meet with resistance and obstacles:

- Culture shock

The European transport sector is made up a myriad of different companies, which have interests which are sometime confused and divergent. The sector is governed, moreover, by a strong European regulatory regime and numerous national ones. This creates a highly complex situation for the big American digital platforms which depend on the contrary on the simplification of procedures and deregulation. There is therefore a natural incomprehension and mistrust between the transport sector and the platforms. Clear principles of governance need to be found before any overall optimisation can be achieved via economies of scale.

- Shock to transporters' economic model

The change in the rhythm of vehicle renewal and the introduction of new ways of marketing rolling stock (hydrogen-powered lorries can be made available for hire on a per kilometer basis) will have a major impact on transporters. The existing business model, which is often based on exceptional profits generated by the resale of equipment, will find itself struggling and there will be a negative impact on liquidity. Financial support will undoubtedly be necessary to get over the hump.

- Investment shock

Implementation of an ambitious clean energy supply policy, the development of inter-modality via the railways and rivers and the development of recycling circuits will require major infrastructure investment. With budgets already tight, countries will hesitate or even resist to making these investments.

5- Conclusions

The transport sector is both a participant and an onlooker in a linear economy which is struggling to make the leap into the circular economy. The components which will make this transformation possible already exist, as do individual consciences, but progress is slow.

It seems clear that a simple technological response, as formulated by legislators and the European Commission, is inadequate and that it will be necessary to supplement it with an essential but forgotten element, namely man himself: European citizens who are both voters and consumers, haulers who provide the service and the transport partners who play their different roles throughout the supply chain. A whole range of actions, starting with awareness and including training, taxation and a system of rewards, which will give recognition and recompense to those involved, are and will remain indispensable.

Our latest articles

-

Subscriber 3 min 24/02/2026Lire l'article -

Hapag-Lloyd - Zim: a shipping deal with geostrategic implications

Lire l'article -

European road freight: the spot market is stalling

Lire l'article