The Asia-Europe Railway has been in the limelight since the outbreak of the pandemic, with a sharp surge in freight volume during the past eight months. However, this success is now hampered by its level of congestion.

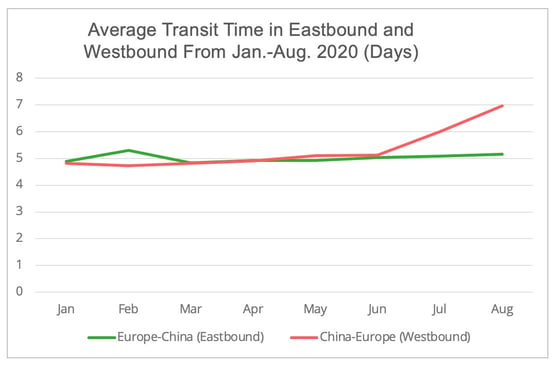

In the past eight months, the volume of freight (TEUs) via the Asia-Europe railway increased by 49.3% on a year-on-year basis [1]. However, during the summer period, shippers faced a serious challenge on this lane: congestion. The problem mainly occurred on westbound shipping from Asia to Europe. According to the Eurasia Rail Alliance Index developed by “United Transport and Logistics Company – Eurasian Rail Alliance” (UTLC ERA), the average transit time from China to Europe has shown a significant increase since June (figure 1).

Figure 1 - Datasource: Eurasia Rail Alliance Index

From the end of June to mid-July, severe congestion occurred at the China-Kazakhstan border, in some extreme cases with more than a 2-week delay. As a result, in June, the Chinese National Railway Administration ordered Chinese carriers to cut capacity, mainly on the newly added lines for cargo heading to Europe and central Asia in order to restore the flow. It has recently been reported that there has been some relief to the congestion in Alashankou.

The increasing backlog further up the line added to the difficulty in meeting demand for capacity already encountered at the Polish/Belarus border town of Małaszewicze, resulting in additional congestion in mid and end August. Congestion at Małaszewicze, which handles around 90% of railway cargos between China and the EU, has been an issue in the Eurasian rail freight for years.

Seeking Alternative Routes

As an instant response, shippers and forwarders are seeking alternative routes to bypass the congestion point. To avoid Małaszewicze, the short-sea shipping route between Kaliningrad and Rostock has gained in popularity. Four months after the launch of the route in April, the export of containerized volume from Kaliningrad has doubled compared to last year (figure 2). However, for the moment shipping volume via this route remains marginal, and its cost is also reported to be higher than via Małaszewicze.

Figure 2 - Datasource: Kaliningrad Sea Commercial Port

Reasons behind the congestion

Overall, congestion is an outcome of two factors.

- Firstly, an infrastructure bottleneck that is incompatible with the sudden surge in cargo. A smooth transfer of cargo from one gauge to another is limited by capacity. To address the limitation in infrastructure, a number of expansion projects have been carried out. For instance, in June, PKP Cargo obtained the contract to expand Malaszewicze terminal’s capacity, this project was funded by both the Polish state and the EU. However, the project is planned to start in late 2021 and will not be completed until 2028, and as such will not address the congestion in the short term.

- Secondly, the wagon shortage for westbound traffic (Asia to Europe), due to the imbalance in volumes between eastbound and westbound traffic, is another major reason behind the congestion of shipments to Europe. In the first six months of 2020, despite a significant increase in eastbound shipping, its volume remains at 60% of that for westbound shipments. As a result, a sustained growth in eastbound shipping lies at the center of the future development of the Asia-Europe Railway.

Mixed patterns in Eastbound shipping

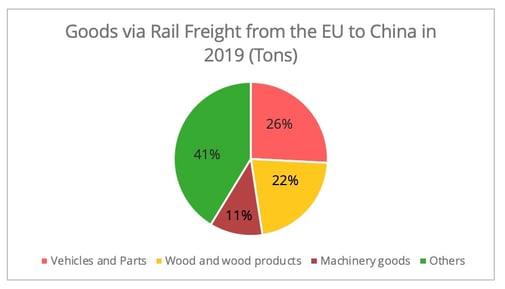

The eastbound demand can be more fragile than that of westbound. Not only is the volume westbound larger due to the China-EU trade structure, but also there is a political drive behind westbound shipping. Based on the analysis of the structure of goods shipped eastbound via rail freight (figure 3), we see a mixed picture.

Figure 3 - Datasource: Eurostat

On the one hand, the gloomy Chinese market for imported automobiles, the largest part of eastbound shipping, casts a shadow on its long-term vision. The automotive sector is among the industries that are the most affected in the pandemic. For the moment, the Chinese market for imported automobiles is still struggling to recover. According to the Chinese Automobile Dealers Association, from January to July 2020, imported passenger automobile retail plummeted by 20.4% compared to 2019.

On the other hand, potential growth may be seen in some other sectors.

- Firstly, intermediate machinery and parts shipped via rail has the potential to generate growth. Machinery goods make up the third largest section of Eastbound shipping (in volume). In the first half of 2020, the shipment of intermediate machinery and parts via rail has surged. For instance, the freight volume of roller bearings via rail was 6 times that of last year. The recovery of Chinese manufacturing activity and the less disrupted railway freight during the pandemic contributed to this phenomenon. Although the growth rate of shipment of intermediate machinery parts via rail has been slowing down since May, the increased overall demand in this sector may lead to a steady increase in demand eastbound.

- Secondly, the booming cross-border e-commerce to the Chinese market may attract more eastbound railway cargos. In the first half of 2020, Chinese e-commerce imports increased by 24.4%. European countries are among the biggest suppliers of Chinese platforms. In 2018, six out of the top ten exporters to the Chinese cross-border e-commerce market were European countries: Germany, UK, Netherlands, Switzerland, Italy, and France. Some popular goods are milk powder, infant products, and cosmetics. The utilization of railway freight to facilitate the cross-border e-commerce is an important part of China’s policy kit to boost its foreign trade, though this policy may have more impact on westbound shipping than eastbound.

- Thirdly, in the long term, reefer shipping by rail can grow the eastbound volume, though not in the short-term. On the one hand, China's strong demand for meat and the recently relaxed Russian regulations on shipping European food through its territory serve as the necessary and sufficient conditions for potential growth in this trend. On the other hand, China, South Korea, and Japan have temporarily suspended the import of German pork due to the recently detected swine fever in Germany, the second-largest EU exporter of pork to China in 2019.

Of course, a more balanced pattern of shipping in both directions cannot be achieved overnight. As a result, other strategies have been initiated to address westbound congestion. For instance, UTLC ERA implemented a reduced tariff for eastbound shipping of empty 40-foot and 45-foot containers as part of regular trains, hoping to reduce the container shortage for freight leaving China. Also, starting from July, China launched a “digital port” pilot project aimed at enhancing the degree of automation in railway freight to facilitate shipping.

[1] Calculated based on the data provided by the Chinese National Railway Administration.

Ganyi Zhang

PhD in Political Science

Our latest articles

-

7 min 03/03/2026Lire l'article

-

Subscriber France: Road transport prices remained almost stable in January

Lire l'article -

Hapag-Lloyd - Zim: a shipping deal with geostrategic implications

Lire l'article