-1.png?width=730&height=395&name=visuels-rs-market-insights%20(1)-1.png)

In 2021, the UK theorized a political desire to develop its relations with the Indo-Pacific region. However, trade figures show that results remain limited for the time being.

By positioning itself as a European country with global interests, the UK presented its Indo-Pacific tilt in 2021, aimed at expanding its comprehensive connection with this strategic region. However, the trade statistics show the gap between tangible trade connections and political engagement, at least for now. Following the UK’s Indo-Pacific tilt, one highlight of its pivot towards Asia is definitely its accession to the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-pacific Partnership (CPTPP) on March 31st, 2023, making it the very first non-founding member to enter the trade agreement.

The membership nonetheless carries more political significance than economic benefits. On the one hand, the deal allows the UK to access the trade block with 99.9% of products tariff-free and to enter trade deals with members that it previously has no FTA with, like Malaysia (Table 1). But the expected GDP growth in the the long term resulting from membership of the CPTPP (with the current members) is likely to be only 0.08%, according to the UK government projection[1]. One reason is that the UK already has free trade agreements with most members. Nonetheless, joining the trade block could give the UK a unique opportunity to assert its influence in the region, as neither the US nor China is a member, though the latter has already applied for membership to the pact.

Besides the CPTPP, the UK is cementing its relationship with India – a country in the spotlight – by creating a strategic partnership and negotiating a free trade agreement. Apart from the economic engagement, the UK also seeks to assert more influence in the region's security as it is part of the Australia-UK-US defence partnership.

Table 1 - © Upply

Undoubtedly, the UK does not shy away from its strong intention to engage in this region. So far, to what extent has the UK's pivot to Asia strategy manifested in the trade connections? Based on the latest trade statistics, this paper would like to scrutinize the UK’s trade connection with the Indo-Pacific region.

UK’s Trade Connection with Indo-Pacific since Brexit

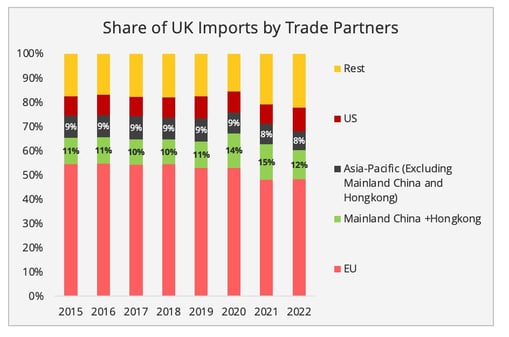

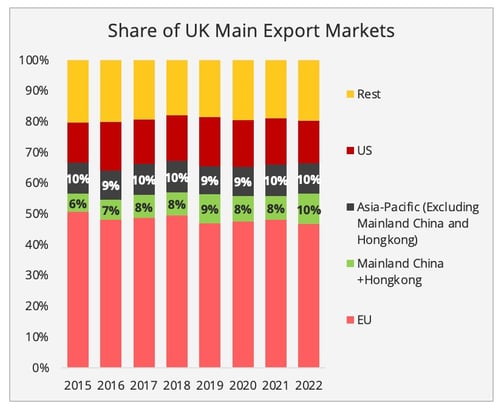

Following the Brexit referendum in 2016, we have seen the UK's trade in goods slowly but steadily diversify away from the EU with a slight increase of the share from Asia and the US, however, its trade with the EU continues to represent nearly half of the trade value.

- A strong relationship with China

In terms of the UK's relationship with Asia, the trade connection between China and the UK has been strengthened over the past few years. In 2022, China was UK's second-largest supplier. China’s share in UK’s imports has dwindled from 15% in 2021 to 12% in 2022, this can, however, be primarily attributed to the surging energy cost, which increased the weight of Saudi Arabia and the UAE in the UK's imports (Figure 1). As the UK's fifth largest export destination, China has also seized a considerable share in the UK's exports, from 7% in 2016 to 10% in 2022 (Figure 2).

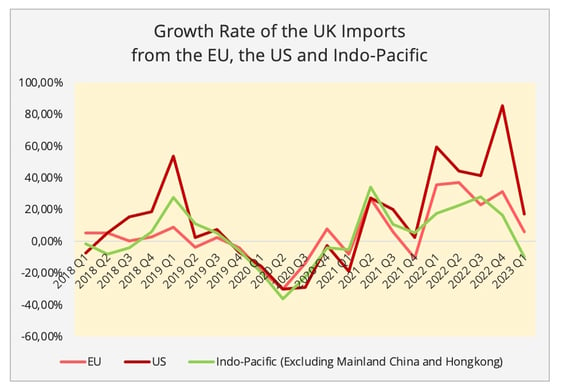

Conversely, the UK’s trade with other Asian countries seems to be at a standstill, with only a modest increase. However, it is worth noticing that the growth rate of the UK's trade with these countries has outperformed that of China (mainland China and Hongkong) in 2022. This trend has continued in the first quarter of 2023. Although weak demand curtailed British imports from Asia, its drop in imports from China (down 25%) was much greater than that of the rest of the Indo-Pacific (10%).

Figure 1 - Data Source: Office of National Statistics, UK.

Figure 2 - Data Source: Office of National Statistics, UK[2].

- A rise in friend-shoring

In the meantime, compared to the pivot towards Asia, friend-shoring seems to be more significant. Following the end of the Brexit transition period, as of the second quarter of 2021, the UK's imports from the US have outpaced those from both Indo-Pacific and the EU, this is partially driven by the surging demand for US energy supply (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Data Source: Office of National Statistics, UK.

- Industries with more Asian Connections

An analysis by industry shows that tightened trade connections occurred in the automotive, mechanical machinery manufacturing, and beverage sectors. Nonetheless, a closer bi-directional trade connection has only taken place in the automotive industry.

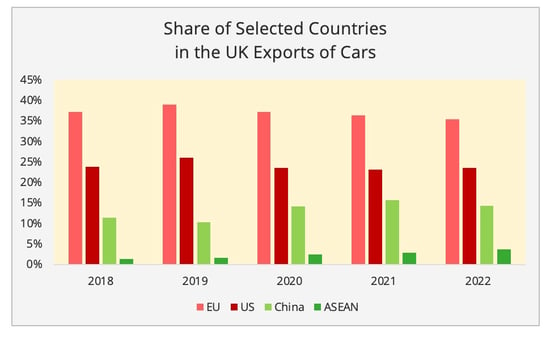

The dynamism of trade between UK and Asia in the automotive industry is particularly discernible. Although UK vehicle exports have fallen for five consecutive years, especially to the EU and the US, they have remained relatively stable to the Chinese market. Consequently, the Chinese market now accounts for around 15% of its total automotive exports.

Furthermore, the emerging consumer market in Southeast Asia also led to a doubling of exports of UK-made vehicles to this region in terms of value, however, the market marginal share remains marginal (4%). In the past four years, ASEAN has surpassed both Japan and South Korea, making it the second largest market for British cars in the Indo-Pacific. The surge is particularly noticeable in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand, whose demand has respectively been multiplied by 6, 1.5, and 1.9 in the past five years.

As for imports, China's ambition to champion the global EV industry is well reflected in the UK market. By 2022, Chinese-made EVs accounted for almost one-third of the UK's Battery-electric car sales, while the share was only 1.9% in 2019, according to the European Automotive Manufacturer's Association.

Figure 4 - Data Source: Office of National Statistics, UK.

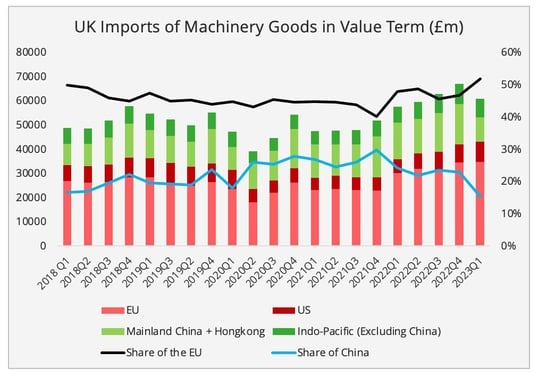

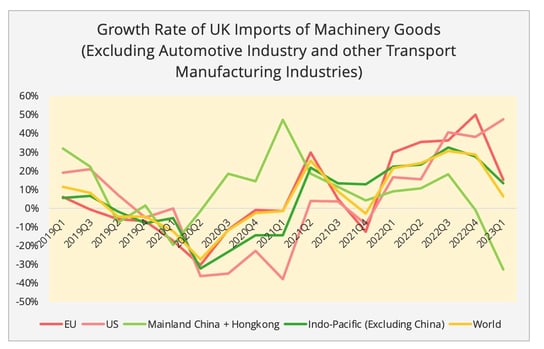

Besides the automotive industry, the UK has been sourcing more machinery goods from Asia, primarily China, especially since the global pandemic. At the same time, the EU's share in the UK's imports has risen radically in this sector since the second half of 2022 (Figure 5). The curbed demand and the Zero-Covid policy in China in force at the time jointly contributed to the phenomenon (Figure 6).

Figure 5 - Data Source: Office of National Statistics, UK.

Figure 6 - Data Source: Office of National Statistics, UK;

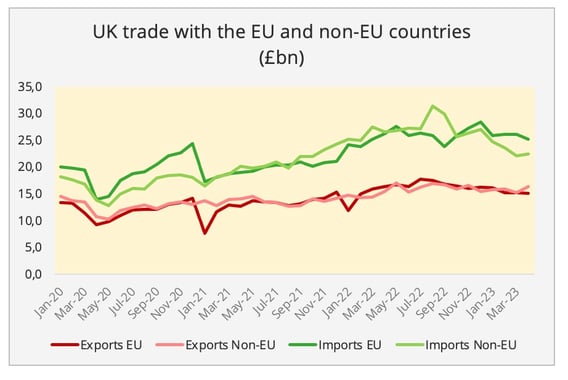

As an outcome of the recent development in this sector, the UK’s total imports from the EU surpassed its demand from non-EU countries again since the fourth quarter of 2022 (Figure 7), this is the first time this has occurred for such an extensive period since the end of the post-Brexit transition period.

Figure 7 - Data Source: Office of National Statistics, UK.

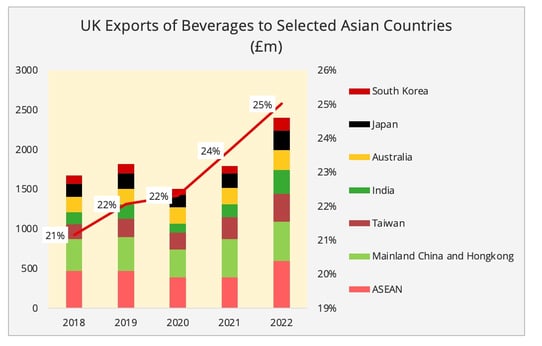

In terms of UK exports, its beverages, mainly alcoholic drinks, saw a rapidly expanding Asian market, which now accounts for a quarter of its exports (Figure 8). On the one hand, in 2022 the UK's sale of beverages to the US market recovered to its 2018 level after they mutually agreed to remove the 25% tariff on Whisky. On the other hand, the UK's beverage industry saw much more significant progress across all surveyed Asian countries or regions for this product. In fact, ASEAN in 2022 has become the UK's second largest non-EU market for beverages, second only to the US. Besides Asia, Latin America is another region that witnessed an emerging demand.

Figure 8 - Data Source: Office of National Statistics, UK.

Looking Forward

Overall, despite the UK’s strong strategic interests in the Indo-Pacific region, the progress in trade remains limited, except for its trade with China and ASEAN in some fields. Indeed, more significant changes will need time to manifest themselves, especially in light of the current challenging world economy. In the latest World Bank economic forecast, the 2024 GDP projection has been downgraded to 2.4% from the 2.7% figure published in January.

For trade activities, besides the aforementioned macro factors, the trade progress with the Indo-Pacific region can also be overshadowed by the stronger friend-shoring trends, the active transatlantic trade, as well as the recent recovery of imports from the EU, especially in machinery goods. Indeed, the sharp drop in Asian machinery goods does not only occur in consumer products, but also in intermediate goods for further manufacturing. In the meantime, the plummeted EU demand for UK goods also means the UK needs alternative markets, and Indo-Pacific could certainly be one of them, as the statistics of the car and beverage sales to ASEAN may suggest.

Furthermore, the bleak economic projections coupled with geopolitical uncertainties also means more conservative investments. For example, in the post-Brexit period, the UK has been falling behind the US and the EU in attracting EV battery investment, along with several manufacturers closing down their sites in the UK. As such, pivoting to Indo-Pacific and joining the CPTPP could also attract new inward investment flow into the UK from Asia. For example, the reported potential multi-billion pound investment by Indian automaker Tata (also the owner of Land Rover) to build a major EV battery plant in the UK could be positive news for the British automotive industry.

A vital event in the future for the UK’s ability to implement its "Indo-Pacific tilt" could be China and Taiwan's applications to join the CPTPP, especially due to the sensitivity of cross-strait relations. As delicate as the issue is, some analysts suggest this could be a perfect next stage for the UK, a new outspoken member of the pact. It would be able to offer a cover to other CPTPP members such as Australia and Japan, which are reluctant to directly address the issue due to their heavy economic exposure to possible Chinese retaliation. As such, even if the direct economic benefit of the CPTPP could be marginal, the UK's membership in CPTPP may also offer it more leverage to influence the economic dynamics in this region, paving the way for more commercial activities.

[1] In the government assessment, they also offered two other scenarios, one with members expanding to South Korea and Thailand, and another one with additional members of South Korea, Thailand and the US. In both scenarios, the expected long-term contribution to GDP would be 0.25%.

[2] Asia-Pacific (Excluding Mainland China and Hongkong) refer to ASEAN, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, India, Australia, and New Zealand.

Ganyi Zhang

PhD in Political Science

Our latest articles

-

Subscriber 3 min 24/02/2026Lire l'article -

Hapag-Lloyd - Zim: a shipping deal with geostrategic implications

Lire l'article -

European road freight: the spot market is stalling

Lire l'article