The pandemic has resulted in a strong increase in demand for e-commerce since lockdown measures have led consumers to seek more online options. Under the challenges facing global trade, which the IMF predicts will suffer an 11% annual contraction, we analyze in this paper if cross-border e-commerce could be the silver lining of the crisis in international trade.

According to research conducted by Global-e, as of mid-April, cross-border e-commerce for 2020 had increased 11% globally. IATA mentions a 25-30% surge in demand for air capacity. While cross-border e-commerce remains a small portion of total trade, governments also have their eyes on this sector. In this paper, we take the China-EU cross-border e-commerce as an illustrative case, under the new Chinese policy in this sector.

Quick view of logistical challenges

Generally, there are two models for cross-border e-commerce logistics: global delivery and overseas warehouses in or near the country of destination. In comparison with domestic e-commerce, cross-border e-commerce is of course more sensitive to the international transport situation.

For global delivery, it relies on the belly cargo shipment in passenger air transport for small parcels. As a result, the reduction in passenger flights of up to 95% has caused severe disruption to small parcel shipments. There was a shrink in belly capacity for international air cargo of 43.7% in March. A positive signal here might be a tendency to the stabilizing of airfreight rates: a fall in airfreight rates from Asia to Europe was seen for the first time in three months. Apart from the disrupted international transport, changing local regulations can also lead to delays in the shipment of small parcels.

The second model is based on locating warehouses in the destined country, mainly by Amazon (FBA), either third-party or self-owned. This mode turns the B2C business model to B2B2C, meaning first shipping in bulk to the country of destination and then conducting local fulfillment services. The bulk shipment to the warehouses means having a closer link with ocean freight, particularly for less time-sensitive and seasonal large goods, due to the much cheaper cost of ocean freight compared to air cargo. The blank sailings in ocean freight are set to be a challenge for this option.

While the option of overseas warehouses can be a more resilient one in a period of disruption in international shipment if the inventory is there, the change in local regulations could cause disruption. For instance, from mid-March to early April, Amazon’s decision to suspend the entry of non-essential products into their warehouses temporarily froze demand of cross-border e-tailers of this sector. In France, Amazon’s fulfill centers remained closed until May 18th. With the gradual lifting of lockdown measures comes the implementation of protective measures in workplaces, which could continue to affect the operations of these overseas warehouses.

Prospects for China-EU cross-border e-commerce

The strong performance of Chinese cross-border e-commerce in the first quarter, a 34.7% increase contrasting with the 6.4% decrease in exports and imports for the same period, triggered the government's further endorsement of cross-border e-commerce within foreign trade. The latest policy has decided to establish 46 more cross-border e-commerce Comprehensive Pilot Zones, bringing the total number to 105. Companies within pilot zones can benefit from policies that facilitate trade.

Westbound: From China to Europe

In 2018, around 10% of EU e-commerce sales came from non-EU countries, with China being the largest supplier. From 2014 to 2019, the EU online consumers who made purchases from sellers outside the EU increased from 17% to 27%. According to a survey by the International Post Corporation (IPC), the percentage of cross-border e-commerce imports from China to the CEE and Southern European countries was relatively higher than that in Western and Northern European countries. For instance, Spain has been chosen as the gateway for Alibaba’s cross-border e-commerce platform, AliExpress, to expand to the broader European market. Furthermore, Alibaba launched its first smart logistics project, eWTP, in Liege Airport, to expand its European logistics network.

- Railway + Overseas warehouses

Multiple Chinese trade policies issued in April signaled a preference for the logistics model of “China-Europe Railway—Overseas warehouses” in cross-border e-commerce exports to Europe. It uses the Europe-Asia railway freight network to ship in bulk to the warehouses located in the country of destination where delivery is then carried out by local services. The China-Europe Railway freight during the first four months spiked with a 24% growth rate. The orders for the shipping of cargo for cross-border e-commerce via the railway from Chengdu to Europe, one of the most frequently used lines, increased more than eight times in the first two months. A joint announcement by WCO, OSJD and OTIF on May 15th encourages simplified customs procedures for a period of time and will be more good news for railway freight.

Despite the temporary suspension of activities, further expansion of Chinese warehouses in Europe can be envisaged in the mid to long term, with the policy of encouraging joint building and sharing of overseas warehouses. Of course, the relatively high investment and stockpiles in the overseas warehouse option can be challenging for SMEs. Currently, there are over 1,200 overseas warehouses world-wide run by Chinese firms in these pilot zones. Europe is the second-largest destination for the overseas warehouses operated by Chinese firms, after the US.

The implementation of the modernization of EU VAT, scheduled for July 1st, 2021 on cross-border e-commerce, is likely to further encourage Chinese e-tailers to choose to apply the overseas warehouse model over the global delivery option in exporting to the European market, due to the abolishment of the VAT exemption of small consignments up to 22 euros. Of course, another question would be: will the pandemic, to a certain extent, shape consumers’ preference for local or regional online shopping, i.e. intra-EU cross-border e-commerce, instead of extra-EU cross-border e-commerce? For instance, a survey on Hungarian online consumer behavior suggests that nearly half of the respondents, 46%, chose not to use cross-border e-commerce due to the pandemic.

In addition, the VAT rate could reduce the price competitiveness of Chinese products, leading to a lower demand from the EU market. In an IPC survey, over 75% of respondents would choose to reduce or stop purchasing Chinese products if there is a 10-euro price increase when the anticipated VAT reform enters into force.

Eastbound: From Europe to China

As the country with the world’s highest number of cross-border e-commerce consumers, around 150 million (in 2018), Chinese demand for overseas products remains strong despite the pandemic. In February 2020, the transactions of Tmall Global, Alibaba’s cross-border e-commerce platform for the domestic market, surged by 52%.

Among the top 10 exporting countries to Chinese cross-border e-commerce, there were four European countries, three EU member states, Germany, France and Italy, and the UK. Nonetheless, none of them were among the top four countries[1]. European food, wine, cosmetics, and fashion products are the main categories with a high demand.

With the gradual reopening of economic activities, comes the latest List of Cross-Border E-Commerce Retail Imported Commodities (known as the Positive List), which now includes more frozen food and wine items, this could mean a good opportunity for EU food and beverage traders. In 2019, China was the EU’s third largest food and beverage export market, after the UK and the U.S, accounting for 8% of the EU’s total exports in this sector. Furthermore, European goods may benefit from opportunities to further expand into the Chinese market of tier 3 and tier 4 cities, since some of these cities are included in the newly expanded pilot zones and can engage in cross-border importing if qualified.

- Railway + Bonded warehouses

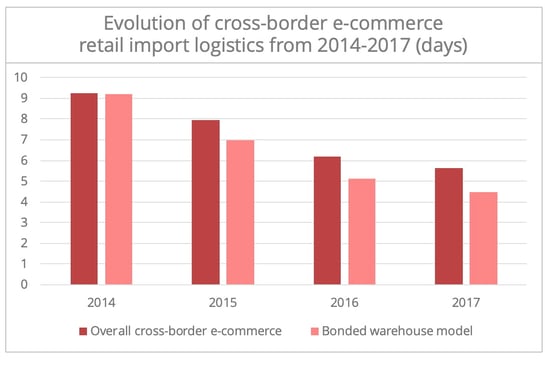

The corresponding Eastbound logistics model to the Westbound “Railway + Overseas warehouse” is the “Railway + Bonded warehouses” model. In terms of delivery time, the bonded warehouse option is swifter (figure 1) than global delivery, with faster customs clearance. It is normally suitable for products with consistent demand, such as milk powder. A downside of bonded warehouses is that items can be more limited than the global delivery model.

Bonded warehouses can be more resilient during a period of huge disruptions. During the temporary suspension of overseas manufacturing activities due to lockdown measures and the disrupted international shipments, many Chinese cross-border e-commerce importers had to primarily rely on their inventory in bonded warehouses to meet domestic demand.

Figure 1: Source: Report “Chinese Imported Consumer Goods Market Report” by Deloitte and Ali Research

- Overseas warehouses + Air cargo

The latest policy of building and sharing overseas warehouses is also likely to contribute to the “overseas warehouses + air cargo” model for exports to the Chinese market. In some cases, for instance milk powder, Chinese consumers may find global delivery to be a more reliable option than shipment via domestic bonded warehouses due to quality concerns.

In 2019, Tmall Global, Alibaba’s cross-border e-commerce platform for the Chinese market, launched its Tmall Overseas Fulfillment service. This is in line with the growth of integrated logistics services for the major Chinese e-commerce platforms, for instance, Cainiao Logistics and JD logistics, the subsidiaries of Alibaba and JD.com, respectively.

Furthermore, an integration of the two models is also applied to optimize the supply chain for certain products, for instance fresh food. The pandemic and the expanded Positive List have also further accelerated demand for imported fresh food via cross-border e-commerce. In this case, an integrated refrigerated logistics network "Overseas warehouses + Air cargo + Bonded warehouses" can be observed.

[1] The top four countries are the US, Korea, Japan, and Australia based on the joint report from Deloitte and AliResearch.

Ganyi Zhang

PhD in Political Science

Our latest articles

-

Subscriber 3 min 24/02/2026Lire l'article -

Hapag-Lloyd - Zim: a shipping deal with geostrategic implications

Lire l'article -

European road freight: the spot market is stalling

Lire l'article