The Russia-Ukraine war has radically changed the rail freight connection between China and Europe via the Northern Corridor. This article examines the development in the first seven months of 2022, concentrating on the period following the outbreak of the conflict.

According to statistics from China Railway, from January to July 2022, China Railway Express, the official name of the rail freight network between China and Europe, recorded a shipping volume of 869,000 TEUs, which represents a 4% year-on-year increase [1]. This rise can be attributed to the burgeoning rail freight demand between China and Russia, driven by a 30% spike in trade between these two countries in the first seven months and by the suspension of services by major maritime carriers in Russia.

The decline in China-EU flows

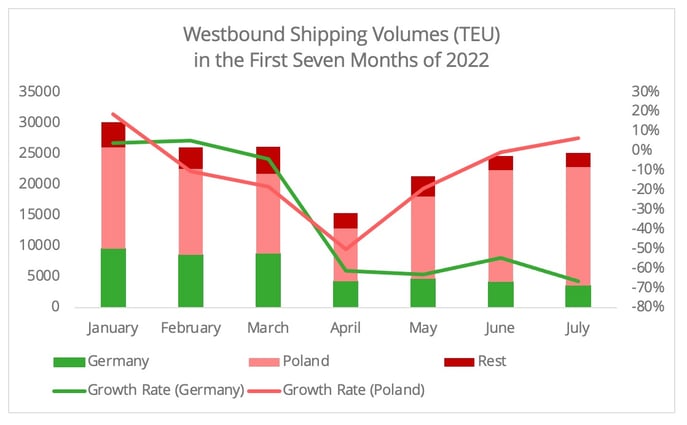

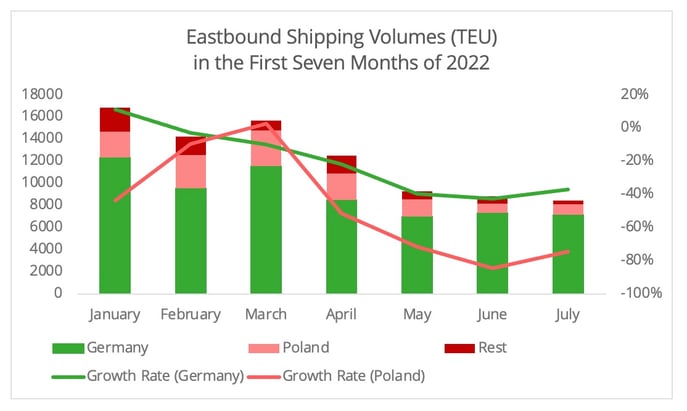

Over the same period, the shipping volume between China and the EU via the Eurasia route (China, Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, EU/Poland), which accounts for the majority of volumes, has logically decreased, by 24% westbound and 35% eastbound (Figures 1 and 2), despite the fact that rail freight is not affected by the sanctions decided by the EU. More specifically, flows to and from Germany, which accounted for 45% of volumes in 2021, fell by 21% in the east-west direction and 38% in the west-east direction.

In contrast, despite the overall decrease, westbound shipping to Poland has been picking up since May (Figure 1). In July in particular, for the first time since the war, volumes to Poland grew by 6.6% year-on-year, while volumes to Germany fell by 66%. This difference is related to the fact that Poland serves as a transshipment hub for distribution to other European destinations, rather than as a final destination, but the trend is nevertheless interesting to observe.

Figure 1 - Data Source: Index 1520

Figure 2 - Data Source: Index 1520

A double explanation for the recovery in volumes

The recovery in volumes is primarily due to a recovery in the main products transported by rail freight, even if it remains modest. This is seen mainly in the sector of machinery goods Westbound to the EU (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Data Source: Index 1520 [2]

The recovery is also fueled by the emergence of new flows in both directions. Even though volumes are modest compared to those of the primary commodities transported by rail, such as machinery goods, their double-digit growth is nevertheless remarkable.

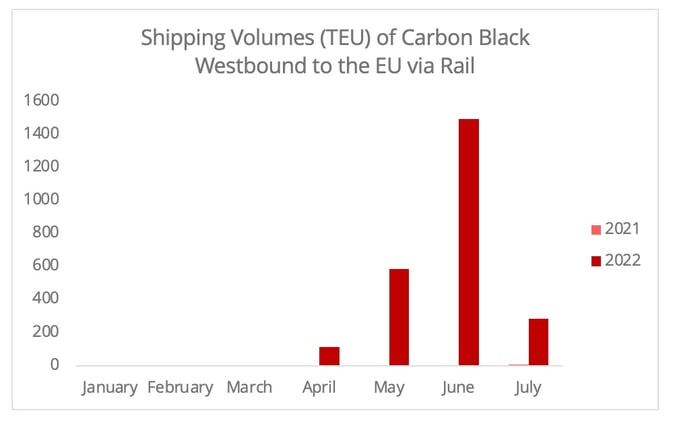

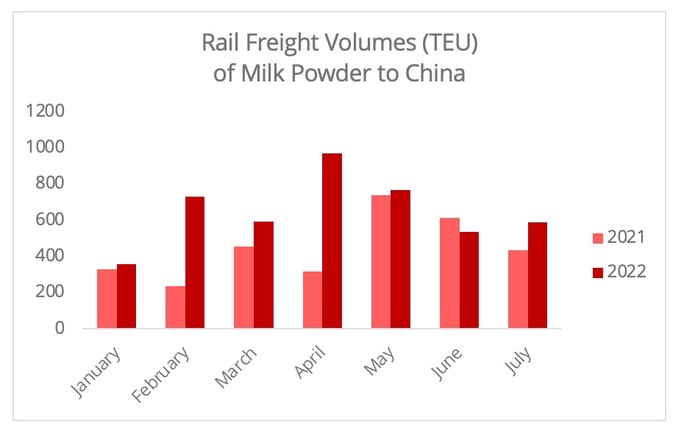

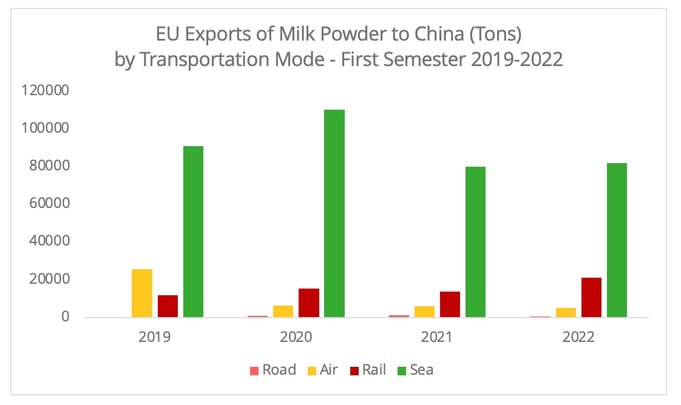

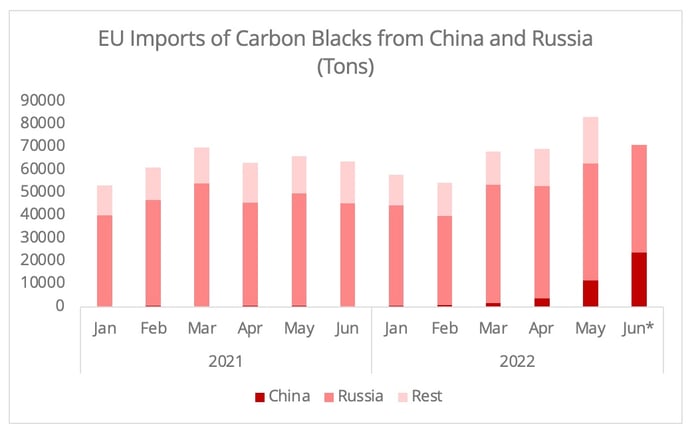

Westbound the flow of new products include carbon black (Figure 4) and leather goods. In the eastbound direction, shipping volumes witnessed a 45% increase in milk powder (Figure 5). The share of this product in total eastbound flows, from January to July, has increased from 2% in 2021 to 5% in 2022.

Figure 4 - Data Source: Index 1520

Figure 5 - Data Source: Index 1520

The arrival of new flows can be explained by the improved efficiency of the Eurasia route, itself the result of the weakening of demand. Several media have suggested this explanation, in a context of the continued disruption in maritime freight. This is particularly the case for shippers of time-sensitive products.

The increased volume of milk powder via rail freight suggests that it is not just maritime freight, but also reduced airfreight capacity may have diverted shippers to the rail option (Figure 6). Comparing the first semester of 2019 and 2022, the shipping volume of milk powder via air freight has dropped by 80%. Conversely, the volume via rail freight has increased 79%. Undoubtedly, Russia’s lifting of the shipping ban of European food through its territory in 2019 is the reason for this shift. Considering the concerns regarding securing food supply, the significant increase of milk powder transported via rail freight this year can be also seen as a desire to avoid disruptions in logistics chains caused by the Shanghai lockdown. The surge in rail freight volumes correlates to this event (Figure 5).

Figure 6 - Data Source: Eurostat [3]

Of course, in some cases, the improved efficiency of rail freight did not solely contribute to the new pattern. It is also coupled with companies’ decisions to increase inventories to hedge against the unpredictability of their situation.

Taking the example of the increase in shipments of carbon black by rail freight. The war has driven EU manufacturers to diversify the sourcing of carbon black, over 70% of which had been supplied by Russia in 2021. The conflict has not reduced the absolute volume of Russian carbon black going to the EU. However, the stockpiling effort to improve resilience has resulted in a surge in imports of carbon black from different suppliers, especially China, in the past few months (Figures 7 & 8). In May 2022, 14% of the EU’s imported carbon black came from China, compared to less than 1% the previous year. Moreover, carbon black is a complex product for ocean carriers to transport, due to safety issues [4] and the cleaning of containers after use. This factor may also have pushed shippers to divert to rail freight, especially at a time of ocean freight capacity shortages.

Figure 7 - Data Source: Eurostat [5]

Figure 8 - Data Source: Eurostat

The outlook for the Northern Corridor

Indeed, it is hard to reach an accurate assessment of the future for rail freight between China and the EU via the Northern Corridor. On the one hand, it is unlikely that transport volumes will return to pre-war levels in the near future, given the duration of the conflict and the radically transformed relationship between Russia and the EU. On the other hand, the analysis above indicates that the impact of the war on China-Europe rail freight is not one-sided but multifaceted. The following factors could influence the prospects for the Northern Corridor.

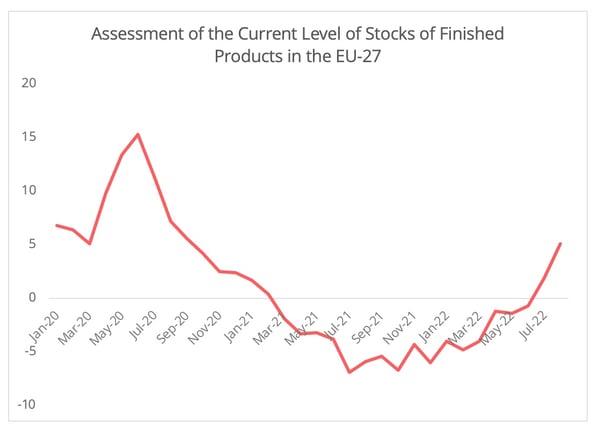

- First, the gloomy global economic outlook for the second semester of 2022 will inevitably affect rail freight demand. The record high level of inventories in the EU over the past two years (Figure 9), driven by multiple factors including an easing in consumer demand, and companies' earlier-than-usual orders, could flatten the overall demand from China in the second semester.

Figure 9 - Data Source: Eurostat [6]

- Secondly, the issuance of the long-awaited policy by the Chinese Ministry of Commerce on supporting electric vehicles (EV) via rail freight may inject new demand. In recent years, championing EV exports has become one of the China’s principal industrial strategies, with Europe being the targeted market. In the first semester of 2022, Chinese exports of electric vehicles to the EU increased by 125%, with Belgium and Slovenia being the primary destinations. In terms of value, China's share of EV imports to the EU market in the first semester of 2022 has increased to 28%, up from 13% in 2021[7]. Obviously, the facilitation of Chinese EV exports to Russian and EU markets will mainly favour Westbound flows.

- Thirdly, although there are emerging infrastructure projects on alternative rail connections, none are likely to prove to be a substitute for the Northern Corridor in the near future. For example, the Middle Corridor (Trans-Caspian Route) has seen substantial growth this year, due to the disruption caused by the war in Ukraine. However, its limited capacity suggests that the Middle Corridor is more likely to function as a complementary service. Particularly as the Chinese government, the essential actor in the early promotion of rail freight connections, is relatively quiet about the Middle Corridor. Today, China’s interest is focused on the resumed China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway (CKU) project, which is back in the spotlight with the signature of an agreement in Samarkand in September, after more than two decades of discussion. The project, which is to start construction in 2023, will bypass Russia and become the shortest rail link between China and Europe. Undoubtedly, this route could have significant long-term potential. However, political and economic challenges may hinder the implementation of this project. The interests of the three nations are not fully aligned. In addition, public opinion in the two Central Asian countries are sometimes reserved towards Chinese investment.

[1] The statistics issued by China Railway usually include products to the EU and non-EU European countries, including Russia and Belarus, as well as central Asia.

[2] The data here includes both HS codes 84 and 85.

[3] This graph is based on Extra-EU data by mode of transport. Transport here refers to the mode of transport used at the time of crossing the EU border. Therefore, this data may not provide the most accurate information on transport volume by mode of transport in China-EU trade, but it is a good reference for the evolution of transport volume. The same applies to the data in Figure 8.

[4] For further details regarding the security regulations, please find, for instance, the customer advisory from CMA CGM as a reference. Of course, there are also strict policies regarding shipping dangerous goods via rail freight.

[5] Due to data availability, we have only presented the import of carbon blacks from Russia and China in June.

[6] Here, the value refers to the stock of goods held by firms in the EU.

[7] These figures are calculated on the basis of Eurostat and HS code 8703.80.

Ganyi Zhang

PhD in Political Science

Our latest articles

-

Subscriber 3 min 24/02/2026Lire l'article -

Hapag-Lloyd - Zim: a shipping deal with geostrategic implications

Lire l'article -

European road freight: the spot market is stalling

Lire l'article