China-EU rail freight via the Northern Corridor has seen a 34% drop in volumes shipped in 2022, due to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and an increase in maritime competitiveness. Some markets are nevertheless promising.

2022 was undoubtedly a challenging year for China-EU rail freight. The Russia-Ukraine war has drastically changed the market. The main route, the Eurasian Route via the North Corridor, experienced a 34% drop in shipping volume in 2022 (- 33% Westbound and - 35% Eastbound). The monthly evolution of the volume and nature of the products transported, nonetheless, tells a more complex story than just a pure decline of the China-EU rail freight market.

In 2022, the rail freight between China and the EU on the Eurasian corridor was both more concentrated and more diversified.

- The market was more concentrated as volume and capacity concerned mainly one or two major routes. Westbound, the share of volumes on the China-Poland route increased from 50% in 2021 to 64% in 2022. By the last quarter of 2022, it even reached more than 70%. Likewise, Eastbound traffic saw the share of flows from Germany to China increase from 66% in 2021 to 80% in 2022 (90% in Q4)[1].

- Since then, commodities shipped via this route are becoming more diverse. The geopolitical incidents and disruptions in other transport modes have jointly resulted in emerging demands for certain goods, which then have been transformed into rail freight volume. Westbound, the share of machinery goods decreased from 44% in 2021 to 37%, whereas the percentage of the chemical sector which previously concerned less than 3% (2021) rose to 7% (2022). Likewise, in the Eastbound direction, the automotive industry contributed 11%, down from 16% in 2021, while the share of processed food rose from 4% to 9%.

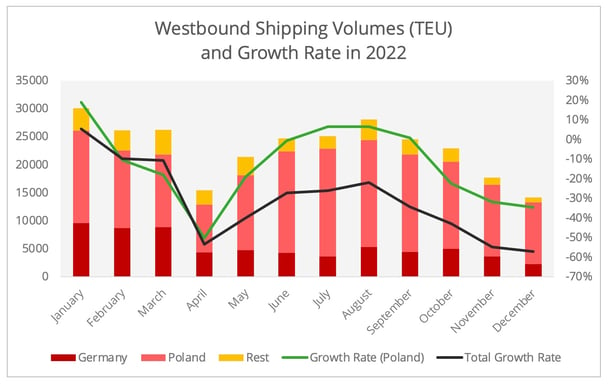

Fluctuating Westbound Flows

Overall, the freight demand Westbound in 2022 can be best described as a "rollercoaster." Following the initial drop after the outbreak of the war, volumes started to resume in May. The recovery persisted throughout the second and the third quarters, before volumes began to plunge again in the fourth quarter. The fluctuation is especially discernible on the China-Poland route. After three consecutive months of growth in the third quarter, the volumes fell sharply by nearly 30% in the fourth quarter, the most significant drop since April (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Data source: ERAI 1520

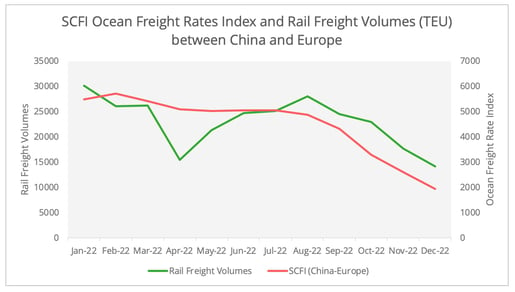

The high volatility of rail freight shipping volumes in 2022 connotes the sensitivity of the China-EU rail freight market to the ocean freight sector (Figure 2). Despite already starting to decline, the ocean freight rates in the first semester of 2022 remained at a high level. The high shipping costs and the capacity shortage, coupled with some rebound demand from China to Europe due to the war, gravitated shippers to the rail freight, which offered sufficient capacity and transit time reliability. However, this situation reverted. Ocean freight rates have fallen back to pre-pandemic levels. The reliability of shipping schedules has also returned to late-2020 levels, which has led shippers to return to sea freight (Figure 3).

Figure 2 - Data Source: Shanghai Shipping Exchange, ERAI 1520

Figure 3 - Data Source: Sea Intelligence

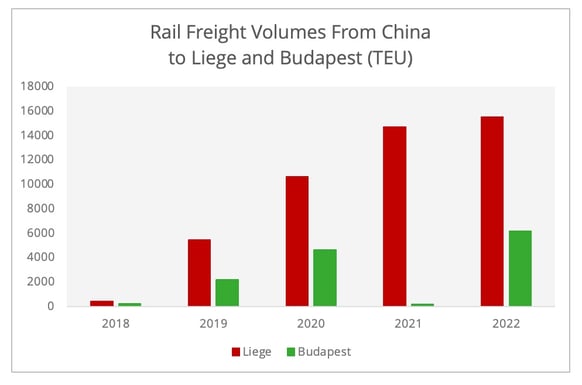

- Noticeable exceptions

In contrast to the overall fall in volumes, there are significant exceptions. The routes from China to Budapest and Liege (Figure 4) have recorded noticeable positive growth in 2022, despite the geopolitical disruptions.

Hungary has long stated its ambition to become a transportation hub connecting Asia and Europe. The volume from China to Budapest via rail freight grew 30-fold from 200 TEUs in 2021 to 6,174 TEUs in 2022. This extraordinary growth can be attributed to a diversion of goods previously entering the EU via the shorter connection from Záhony (through Ukraine and Hungary) in 2021 – to that via Małaszewicze (through Poland and Belarus) due to the war[2]. Besides this diversion, the expansive transport network to reach Central and Eastern Europe and the significant Chinese economic footprint in Hungary may also contribute to the attractiveness of Hungary as a transport hub even during this challenging period.

As for the growth in volumes from China to Liege, it reflects the resilience of cross-border e-commerce activities. Since 2019, Liege has begun to serve as a distribution hub for Alibaba in Europe. Correspondingly, the rail freight shipping volumes from China to Liege have grown by 180% in the past four years.

Figure 4 - Data Source: ERAI 1520

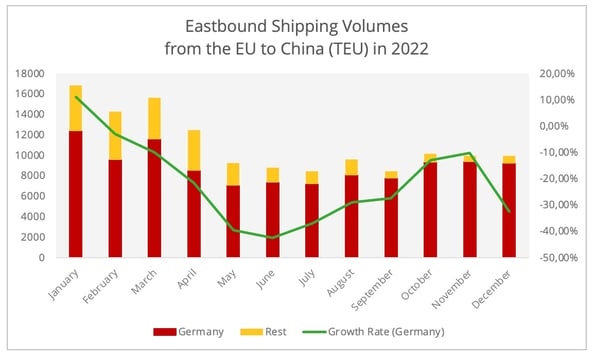

Eastbound: a silver lining at the end of 2022?

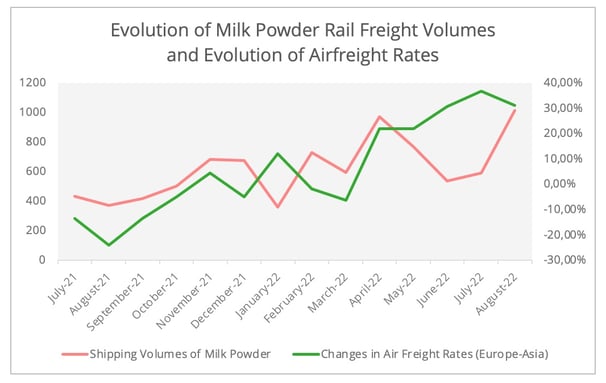

In comparison to the fluctuating westbound demand, the eastbound rail freight market seems to be more "monotone". Volumes have been bleak since the war, with barely any signs of recovery (Figure 5). The only exception is milk powder. This product recorded 52% Y-o-Y growth via rail freight in 2022. This exceptional phenomenon can be primarily attributed to the disruptions in air freight following the war. While milk powder volumes have already been gradually diverting to rail from air freight since the pandemic, the blocked Russian airspace further restrained the air freight capacity from Europe to Asia and pushed up their rates on this route in 2022, accentuating the shift to rail freight (Figure 6).

Figure 5 - Data Source: ERAI 1520

Figure 6 - Data Source: ERAI 1520 and UPPLY

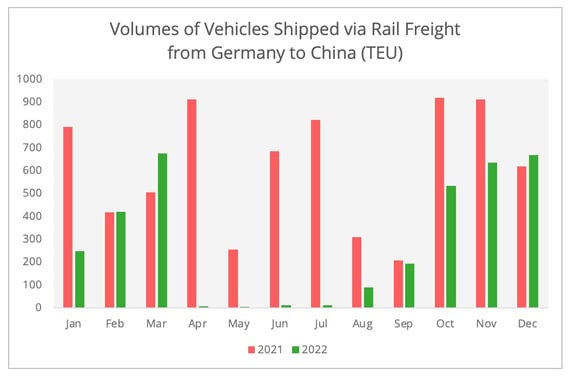

On the other hand, China's sudden reopening in December 2022 could perhaps restore some colour to the Eastbound volumes. From Germany to China, there were some subtle signs of a rebound approaching the end of the year. Apart from milk powder, the automotive industry started to return to the railway, including for the transport of imported vehicles, automotive parts, and tyres[3]. In particular, December 2022 marked a 16% Y-o-Y growth for vehicles shipped from Germany to China via rail, after a fall to nearly zero following the war in Ukraine (Figure 7).

Figure 7 - Data Source: ERAI 1520

2023: Adapting to the New Normal

The year of 2022 offers a perfect illustration of how the vagaries of the ocean freight and air freight market are constantly shaping China-EU rail freight. Entering 2023, some conditions that recently generated changes are likely to dissipate. Air freight connections between China and Europe will gradually resume following the reopening in China. The ocean freight rates are falling to pre-pandemic levels, along with improved reliability. All these factors suggest that the China-EU rail freight market is set to adapt to a new normal.

- Macro Factors

At the macro level, China’s reopening could inject some volume back. However, growth is likely to be more discernible from the second half of 2023, as inflation and curbed consumer confidence will continue to hamper the demand in Europe at the start of the year. In the meantime, the escalation of the war means the geopolitical tensions in 2023 will be a factor that may constantly challenge shipper confidence on this route.

Under the changing economic and political circumstances, the emergence of a more fragmented global supply chain could also have a long-term impact on rail freight volumes between China and the EU. According to the latest Business Confidence Survey by the German Chamber of Commerce in China, localization - "in China, for China" - and supply chain diversification are the two prevailing strategies adopted by German companies to cope with the previous Zero Covid policy and ever-growing geopolitical tension.

Apart from the impact of the macro-economic scenario, there are two issues that may influence rail freight operations that merit particular attention.

- Cross-border E-Commerce

The consecutive growth of the China-Liege route shows an essential role of e-commerce in the China-EU rail freight market. The agreement between Cainiao and DHL, concluded in February 2023 to establish a distribution network in Poland indicates a sustained interest of Chinese investors in cultivating this market. However, this will be confronted with two factors that may overshadow the market.

- Chinese cross-border e-commerce will have to cope with regulatory and logistics challenges. In response to its flat growth rate in 2022 in the EU market, AliExpress cites the VAT regulation that entered into force in 2021 and the logistics disruptions (cost and bottlenecks) due to the war as the leading causes. With no clear end to the energy crisis and inflation, these challenges seem to have become a permanent fixture.

- Changes in buying behaviour show that consumers are increasingly supportive of domestic e-commerce. Indeed, according to the International Postal Corporation's 2022 Cross-Border E-Commerce Shopper Survey, when asked about future e-commerce intentions 74% of respondents will be favouring domestic e-commerce and 58% from neighbouring countries. In contrast, only 38% are willing to buy more from China in the future.

- Electric Vehicle transport by rail

Finally, when discussing the prospects for 2023, the long-awaited green light from the Chinese government to ship electric vehicles (EVs) by rail is unmissable. Particularly as further policy documents have been issued by Chinese authority in January 2023 that support these exports. EVs are no longer labelled as dangerous goods along with other export facilitation measures.

In the last three months of 2022, we can already observe the start of EV shipments Westbound via rail freight, though the volumes remain very modest (232 TEUs)[4]. Rail freight now serves as one pillar to support Chinese ambition to conquer the global EV market. The current tight RORO ocean freight capacity could create a similar diversion effect towards rail freight that we observed in the second and third quarters of 2022. However, we need to keep in mind that large Chinese automotive manufacturers focus more on developing various ocean freight solutions, such as purchasing their own RORO ships or shipping via containers. A question worth asking is that, besides the policy endorsement, to what extent can rail freight continue to be an attractive solution when the ocean freight capacity becomes more available?

Chinese subsidies for new energy vehicle purchases ended in 2022, this may offer some opportunities for imported EVs to compete in the Chinese market, therefore, injecting new demand Eastbound. However, one needs to be aware that the Chinese imported vehicle market has been shrinking over the years. According to the China Automobile Dealers Association, in 2017, China imported 1,216 thousand vehicles, and in 2021, it was down to 940 thousand units. While the disruptions of the automotive supply chain curtailed the imports, a burgeoning consumer preference for domestic brands also contributed to the drop in imports. According to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers, in 2022, domestic brands constituted almost half of the sales of passenger vehicles in the Chinese market.

In this article, we have chosen to focus only on the Northern Corridor. However, it should be remembered that, of course, the growing investment from major players in the logistics industry in the Middle Corridor as well as China's flagship rail freight project to Europe (China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway) that will bypass Russia, will continue to shape the China-EU rail freight market.

[1] The data for the Eurasian Route in this paper is based on the data from ERAI 1520. The data in this paper refers to the Rail Freight Route China-Kazakhstan-Russia-Belarus-EU (often Poland).

[2] This was pointed out in the comment section of a website dedicated to China-Europe rail freight: New Silk Road Discovery. A recent article by Rail Freight.com also pointed out the diversion of routes.

[3] This is based on the trade data of HS code 8703 (vehicles), 8708 (car parts), and 4011 (tyres). N.B. the increased volume of vehicles was not associated with electric vehicles.

[4] This is based on statistics of HS code 870380.

Ganyi Zhang

PhD in Political Science

Our latest articles

-

Subscriber 3 min 24/02/2026Lire l'article -

Hapag-Lloyd - Zim: a shipping deal with geostrategic implications

Lire l'article -

European road freight: the spot market is stalling

Lire l'article