The current coronavirus pandemic has sharply raised the question of European strategic autonomy. In this article, we have chosen to address this topic from two perspectives: the role of Foreign Direct Investments and the reshoring options to create a Pan-European value chain.

On March 10th, the EU Commission published its latest industrial strategy. For the first time, the concept of “strategic autonomy” is addressed in this document. Strategic autonomy, which is originally used in EU’s defense policy, is defined as “reducing dependence on others for things we need the most: critical materials and technologies, food, infrastructure, security and other strategic areas.”

It would seem that this is the ideal time to discuss the strategic autonomy of European industry. The outbreak of COVID-19 has once again raised the question of the EU’s reliance on Chinese imports in various sectors, and not just electronic machinery parts, but also drugs. Chinese production accounts for one third of generic Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients. Even before the outbreak, there had been a growing call from member states for European strategic autonomy in the manufacturing industry, in the wake of growing protectionism around the world and the on-going China-US rivalry in the field of technology. “Thanks to disruptive technologies like 3D printing, Europe also needs to make the most of localisation as an opportunity to bring more manufacturing back to the EU in some sectors”, says the EU’s communication on Industrial Strategy.

In this article, we take a close look at the EU’s approach in addressing this topic. Overall, it can be summarized as:

- for extra-EU, diversifying international suppliers of critical materials and restraining Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) in critical sectors;

- for intra-EU, developing a pan-European value chain for some strategic sectors.

Some of the sectors highlighted in the latest industrial strategy are: digital technology (e.g. 5G), green technology and pharmaceutical industry.

“Dependence” in Strategic Autonomy

Specifically, how do we define “dependence” in terms of strategic autonomy? It can be divided into two parts: the import dependence on global suppliers and dependence on foreign investment in the EU’s strategic sectors.

According to the EU’s Political Studies Association, overdependence on foreign supply and investment can lead to potential risks, such as vulnerability to supply chain disruption due to natural disasters or other incidents, and restrained capability for future development due to forced technology transfer.

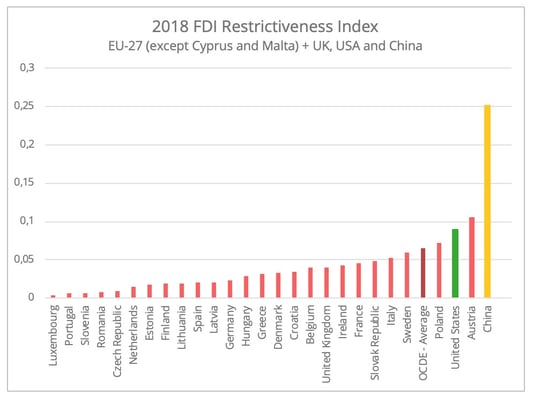

Nonetheless, “reducing dependence” does not mean that the EU should be solely self-reliant, this would be impossible. In fact, the EU has benefited tremendously from its inclusive and open trade policy. The key to strategic autonomy is finding the balance between openness and protection, and to seek reciprocity with its trade partners (figure 1).

Figure 1 - FDI restrictiveness Index (0=open,1=closed). FDI restrictiveness is an OECD index gauging the restrictiveness of a country’s foreign direct investment (FDI) rules by looking at four main types of restrictions: foreign equity restrictions; discriminatory screening or approval mechanisms; restrictions on key foreign personnel and operational restrictions. Data source: OECD

Extra-EU: trade policy tool kit

The EU’s trade policy addresses these two types of dependence in the following ways.

- Firstly, with the aim of restraining foreign investment in critical sectors, such as transport, infrastructure and technology, the EU launched the FDI screening framework in April 2019. This tool could have a particularly strong effect on Chinese investment, which has shown great interest in the transport infrastructure and tech sectors in Europe. However, the regulative power of the FDI screening framework is very limited, since the EU can only request information and issue opinion. As member states have the final say as to what extent the screening framework would go to, the question of its real effect is raised.

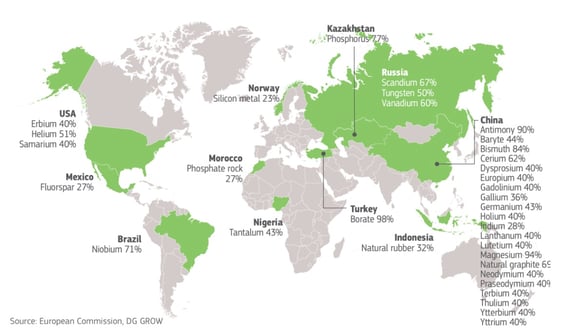

- Secondly, the EU is seeking to diversify its international suppliers of some critical materials through FTAs or political agreement, thus enhancing the resilience of its supply chain. The effort is particularly dedicated to critical raw materials, which are crucial for the EU’s green tech sectors, but are highly dependent on global supply (figure 2). While some of the recent FTAs signed by the EU with Singapore, South Korea and Vietnam, prohibit import tax on raw materials, unfortunately none of them are with the EU’s main suppliers of critical raw materials. As for these main suppliers, it has launched a series of political dialogues to break down some of the barriers to trading these products. While political dialogue can certainly help enhance mutual understanding, the actual impact on increasing the resilience of the supply of these critical materials may not be immediately apparent.

Figure 2 – EU’s dependency on critical raw materials from global market, graph source: European Political Strategy Center

Intra-EU: Reshoring and creating a pan-European value chain

Apart from trade policies, building a pan-European value chain for strategic sectors is part of the EU’s approach to achieving strategic autonomy. For instance, the EU is using the electric vehicle battery industry as a test and reference case for building the pan-European value chain in other sectors. When considering the pan-European value chain, nearshoring or reshoring are very much part of the topic. Furthermore, during the outbreak of Covid-19 in China in the past two months, actively seeking nearshore options is suggested by analysts as one option to cope with the supply chain disruption.

According to the database created by the European Reshoring Monitor, between 2015 and 2018, around half, (95 out of 218) of all the manufacturing industry reshoring cases were from Asia back to Europe. Of these 95 cases, 78% involved a move back from China to Europe. Three characteristics can be defined.

- Firstly, labor-intensive sectors of industry are primarily those that are choosing to relocate to Europe. Specifically, electronic and machinery (28%), apparel and leather manufacturing (14%), and automobile manufacturing (13%) are the three sectors with the highest number of companies shifting some of their manufacturing sites back to Europe.

- Secondly, most companies chose to re-shore to their home countries, mainly western European countries, instead of other European countries. As a matter of fact, out of the 95 cases, only 9 of them re-shored to a different European country than their home country.

- Thirdly, central and eastern Europe (CEE) was the main destination for those companies reshoring elsewhere than to their home country. Out of the 9 cases that re-shored to a different European country, 7, all of which were in the electronic machinery manufacturing sector, were relocated to CEE countries (Poland, Romania, Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia). Cost reduction, in the face of increasing wages in China, and enhancing the efficiency through a shortened delivery distance[1] are the main motives behind the reshoring.

As such, with the EU’s industrial strategy of seeking a pan-European value chain and companies considering alternative options to China, there could also be a great opportunity for the industrial sectors in CEE countries, though this may be a long-term process.

Looking Forward

It cannot be denied how new the latest EU industry strategy is. However, the key will be how to transform strategy into practice. The EU needs to play a more coordinative role among the member states. Afterall, the interpretation of strategic autonomy can be subjective and diverse across industries as well as member states. Perhaps, it will be necessary for the EU to develop measurable criteria or an index as a means to improved evaluation of strategic autonomy in the future, and as such make strategic autonomy more than just an abstract concept on a piece of paper.

[1] Only one case mentioned the impact of China-US trade war. However, there could be a greater number of cases relocating due to this reason in 2019, which is beyond the time spectrum of the database.

Ganyi Zhang

PhD in Political Science

Our latest articles

-

4 min 04/03/2026Lire l'article

-

Heavy goods vehicle registration figures for 2025

Lire l'article -

Subscriber France: Road transport prices remained almost stable in January

Lire l'article