.png?width=730&height=395&name=La%20reconfiguration%20acce%CC%81le%CC%81re%CC%81e%20des%20chai%CC%82nes%20d%E2%80%99approvisionnement%20mondiales%20(1).png)

The continuation of the "Zero Covid" policy in China and the Russia-Ukraine war could accelerate the reconfiguration of the Chinese-centric global supply chain, with a strong dichotomy between diversifying from or strengthening localisation in China.

The current lockdown in Shanghai contrasts with the relaxing of the restrictions among many of China's major trading partners. Such disparity further disrupts the recently recovered global supply chain. This continuation of the "Zero Covid" policy in China, now coupled with the war between Russia and Ukraine, could accelerate the reconfiguration of the global supply chain.

Short term disruption

Strict restrictions in China, including lockdowns, have resulted in serious disruptions in manufacturing and logistics activities in recent weeks.

- Manufacturing Activities

Manufacturing capacity has been severely restrained by the restrictive measures imposed in the big Chinese economic hubs, first in Shenzhen and then in Shanghai. In affected areas, manufacturing activities are usually either suspended or conducted under the "Closed-Loop" model, namely, workers living and working onsite. From late March to mid-April, only around 1/8 of the factories in Shanghai had been able to operate using the “Closed-Loop” model, resulting in extremely limited manufacturing capacity [1]. Consequently, the Chinese Purchasing Manager Index in April 2022 fell to 47.4, hitting its lowest point since February 2020, as stated in the National Bureau of Statistics of China.

The automotive sector is among those hit the hardest, given that Shanghai is China's automotive manufacturing hub. According to the Chinese Association of Automobile Manufacturers, the number of vehicles produced declined by 9.1% in March. Moreover, automotive manufacturers and intermediate goods manufacturers such as Tesla, Volkswagen, SAIC, and Bosch suspended production for most of April. As a result, the automotive supply chain has been exposed to challenging scenarios during the second quarter.

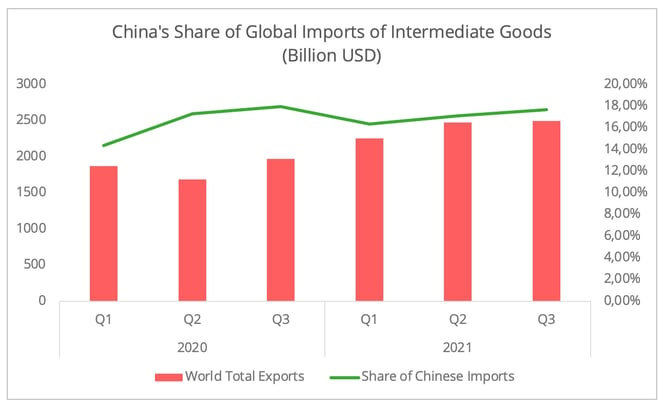

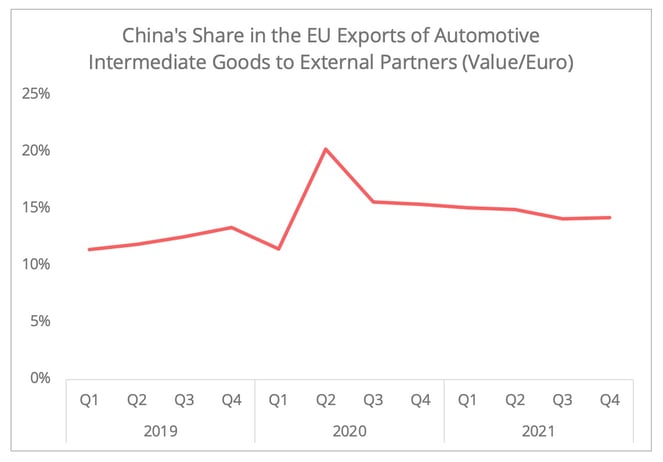

China is not only the largest exporter but also the biggest importer of intermediate goods worldwide (Figure 1). An outcome of the disruption in manufacturing activities is the contracting demand for raw materials and intermediate goods. For example, there was a 2% decline in Chinese imports of machinery goods in March, which contributed 41% of total Chinese imports by value (USD) in the same month. This could curb the export projection of key intermediate goods suppliers for China, such as the EU for automotive intermediate goods. In March, Chinese imports from the EU in the automotive sector dropped by 7% [2].

Figure 1- Data Source: WTO

- Logistics Activities

The logistics disruptions put another constraint on the only recently recovered global supply chain. More than half of the respondents in the flash survey conducted in March by the German Chamber of Commerce in China (AHK) say they have experienced logistics disruption in their operations. Similar findings were reported by 57% of the respondents in the flash survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai (AmCham).

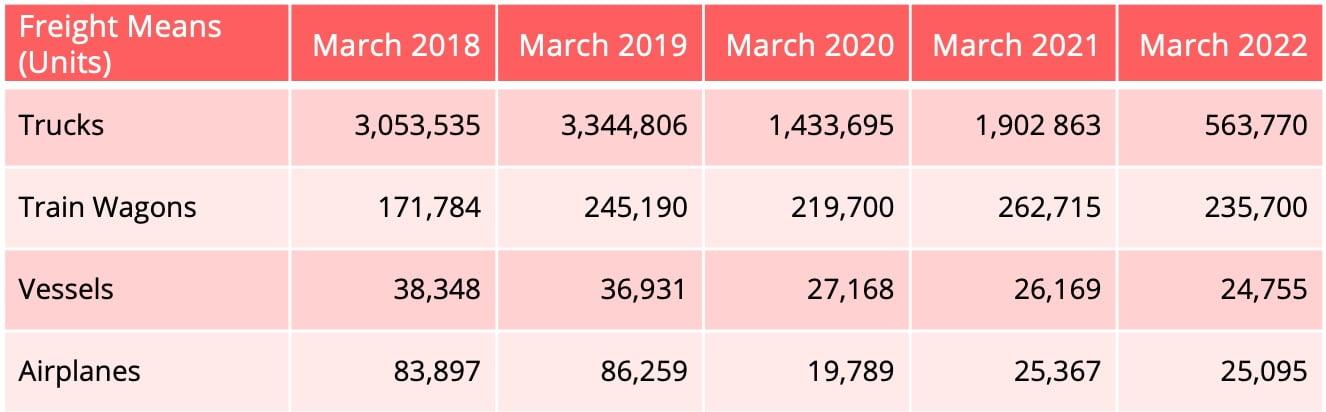

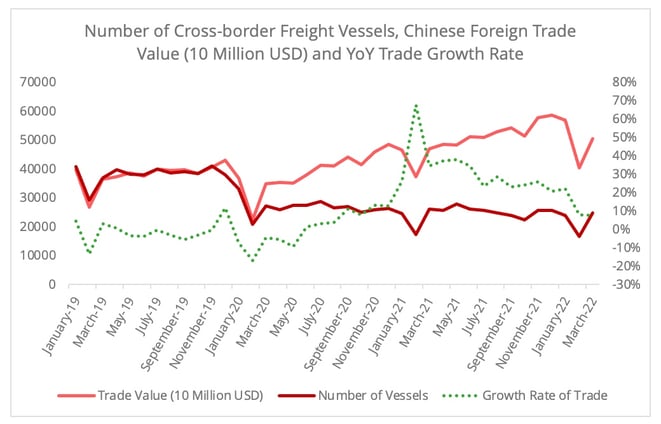

The cross-border cargo movement statistics hit the lowest numbers for March since the pandemic (Table 1). Specifically, the March figure for cross-border vessel movements reached its five-year low. This could be a result of the interaction between restricted transportation following the lockdowns and the slowing down in trade activities (Figure 2). Meanwhile, some blank sailings have been scheduled on the Asia-Europe route following the drop in market demand.

Table 1- Number of Freight Movements for Trade Purposes in March in the Past Five Years [3]. Data Source: China Customs

Figure 2 - Data Source: China Customs[4] and Author’s calculation.

A silver lining on the horizon is perhaps the recent policy to lift certain restrictions on the inter-provincial truck traffic and the issuance of two whitelists allowing the resumption of production in Shanghai (for a total of 1,854 companies). Among the 666 factories on the first list, 37% are automotive manufacturers, and 13% are semi-conductor manufacturers. 80% of the companies on the first whitelist have reportedly resumed their activities, to varying degrees. It may lead to a short-term surge in Chinese imports of intermediate goods if we use the trade statistics following the first outbreak as a reference (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Data Source: Eurostat [5]

However, the widening gap between demand and transportation capacity signals a bumpy road of recovery ahead (Figure 2). Furthermore, the current gradual easing of restrictions in Shanghai could be revised, given that the “Zero-Covid” policy remains the top priority in China with no foreseeable changes, at least not before the second semester of 2022. Chinese local authorities in other regions, with lessons learned from Shanghai, may be inclined to implement radical pre-emptive restriction measures if a rise in cases is reported to avoid potential political consequences. All of these add unpredictability to the domestic supply chains within China. Therefore, for foreign investors, the challenge is not a China with surging covid cases but rather a China committing to the "Zero-Covid" policy.

Long Term Impacts

The ongoing Russia-Ukraine war and the persisting "Zero-Covid" policy may accelerate the global supply chain reconfiguration, as surveys indicate foreign investors are re-evaluating or adjusting their strategies for China.

- The Dichotomization of Supply Chain Strategies

Although it is still too early to be certain about what will happen, we may envisage an accelerated dichotomization of supply chain strategies, namely, on the one hand a diversification in Asia or nearshoring, and on the other an accentuation of the localization policy in China.

Despite "China Plus One" having been the buzzword over the past two years, survey results and trade statistics often indicate otherwise. Localization has been the preferred strategy for foreign investors in China, including onshoring R&D activities and establishing a domestic supply chain. Four times as many respondents chose localization over diversification in the 2021 business confidence survey by the EU Chamber of Commerce in China.

The current Russia-Ukraine war is also steering some investors towards localization. 59% of the surveyed German companies in the AHK flash survey are reported to be considering shifting more production to China. Apart from the attractiveness of the Chinese market, localization is regarded as a risk-hedging choice in light of both the political tension between China and the West, and the logistics upheavals, especially the spiking energy prices.

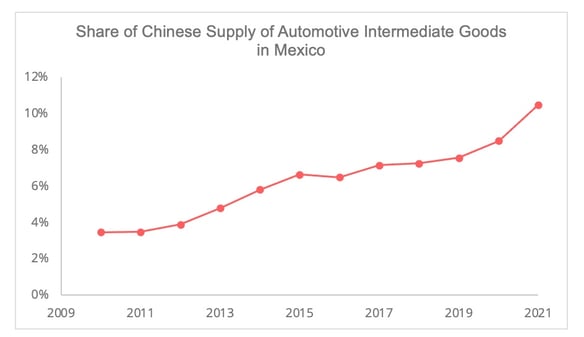

Furthermore, investors are sometimes hesitant to consider nearshoring. It is not only challenging to find ideal substitutions, but also some nearshoring suppliers may still rely themselves on Asian supplies. For example, the Chinese share of Mexico's total imports of automotive intermediate goods increased from the pre-pandemic 7.5% in 2019 to 10.5% in 2021[6] (Figure 4). All these seem to make continuing to rely on Chinese or Asian supply a safer choice in the still chaotic global supply chain.

Figure 4 - Data Source: OECD End-Use Data

Meanwhile, the geopolitical uncertainties and the pursuing of “Zero-Covid” policies are also pushing some investors to break their dependence. The continuity of the “Zero-Covid” policy in China, which is disrupting the domestic supply chain, may penalize the localization strategy. Furthermore, in contrast with 2020, when lockdown was widely implemented, the relaxed restrictions in other countries connote more possible alternative options. However, a standing concern with this strategy will be whether the alternative intermediate suppliers will continue to rely on Chinese supply.

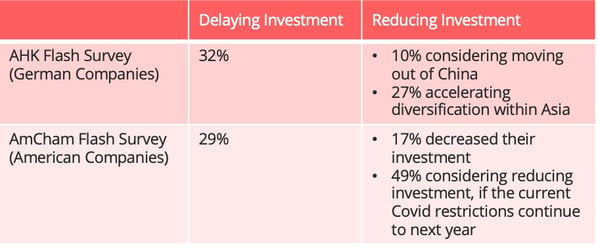

According to a recent report by the Institute of International Finance, China has been experiencing an unprecedented outflow of foreign investment capital since late February 2022. This may correspond to the emergent tendency of foreign investors to reevaluate their China strategy. The AHK flash survey published on March 31st 2022 suggested that 10% of respondents are considering moving their current business out of China, and 27% expect an accelerated diversification within Asia. This contrasts with the AHK 2022 business confidence survey in January 2022, with only 4% of the respondents considering moving out of China. A similar pattern can be observed in the flash survey AmCham (Table 2). Technically speaking, the survey results are not fully comparable, but they do offer us an overview of the changing tendency.

Table 2 - The Survey Result of the Impact on the current surge of Covid in China and Geopolitical Impact, Data Source: AHK Flash Survey and AmCham Flash Survey. AHK survey asked these questions in response to the geopolitical conflict, and the Flash survey by AmCham emphasized the impact of the Covid outbreak.

Of course, the choice is also often industry-specific. Diversification is more likely to occur in sectors with less complicated supply chains and lower value-added products that primarily target markets outside of China. For instance, industries like apparel manufacturing have been moving out of China before the pandemic. Localization is often preferred by sectors with expanding Chinese markets and more complex supply chains, such as electric vehicles. According to the 2021 Business Confidence Survey of AmCham Shanghai, 78% of respondents in the automotive sector increased their investment in 2021, whereas the figure was only 39% in 2020. Ironically, industries seeking to localize are also those the EU and the US are eager to reshore.

- The Chinese “Dual Circulation” strategy

The current Covid outbreak and geopolitical crisis put pressure on the Chinese export-oriented economy, making enlarging the Chinese domestic market an urgent priority. According to China's National Bureau of Statistics, the New Export Orders Index fell sharply to 41.6 in April from 47.2 in March, reaching its lowest level since June 2020.

The abovementioned five-year low March figure for cross-border vessel movement in China can also be seen as an early indicator of a short-term continuation of the slowdown in trade activities recorded since February 2022. Specifically, the scenario could be more drastic in the case of Chinese exports to the EU than to the US. The EU consumer confidence index in April, despite a slight rebound, remains far below the long-term average, whereas the US consumer confidence index, though sliding slightly, remains in expansion at least early in the second quarter.

In this context, the latest Chinese policies amid the current Covid surge, including "Building a United Domestic Market" and “Twenty Measures to Stimulate Domestic Consumption” denote the government doubling down on the “Inner Circulation” part of the "Dual Circulation" strategy, which is China's key economic policy since the pandemic in 2020. This strategy aims to simultaneously stimulate the domestic market (internal circulation) and the international market (external circulation). "Dual-Circulation" is usually interpreted as a signal that China is seeking to be more self-reliant for strategic supplies and in markets.

The heavy focus on “Inner Circulation” could affect the global supply chain in different ways:

- Firstly, it may add the rationale for foreign investors to adopt a localization strategy to seize the expanding Chinese market.

- Secondly, the localization strategy and a more self-reliant China will jointly reduce Chinese demand for external supply of intermediate goods.

- Thirdly, as diversification takes time to implement, the trade deficit between China and its major trade partners could be further fortified. After all, one critical goal of being self-reliant is not to become detached from the global economy but rather for China to maintain its export competitiveness by reducing the reliance on the overseas supply of strategic goods.

[1] The figure refers to enterprises above the designated size, a Chinese statistical term for enterprises with annual revenue above 20 million RMB.

[2] Figure based on the trade statistics of HS Code 87 by China Customs.

[3] The number of cross-border trains is not limited to inbound/outbound trains on Eurasian lines. In 2022, this could also include the newly built train connections between China and Southeast Asia via Laos. These figures issued by China Customs for rail transport is not the number of train trips or cargo trains but the number of wagons.

[4] The February and January 2022 statistics are estimated since China Customs only provided the total number of the first two months in 2022.

[5] The automotive intermediate goods trade data is based on BEC category code 530.

[6] This is based on the OECD end-use data.

Ganyi Zhang

PhD in Political Science

Our latest articles

-

4 min 04/03/2026Lire l'article

-

Heavy goods vehicle registration figures for 2025

Lire l'article -

Subscriber France: Road transport prices remained almost stable in January

Lire l'article