The Asia-Pacific Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP) is beginning to unfold. It brings new dynamics to the global supply chain beyond the region.

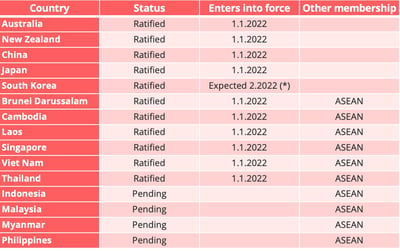

On January 1st, 2022, the Asia-Pacific Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP) entered into force for the ten countries that have ratified it (Table 1). In addition to the analysis of its potential impact on Asia-Europe trade that we presented in a previous article, we examine in this new publication the main provisions of the RCEP, its consequences on the evolution of intra-Asian trade and the repercussions on the ever-evolving global supply chain.

Table 1- The Ratification Status of the RCEP Signatories – (*) This is due to South Korea’s later ratification in December 2021, as the agreement will enter into force 60 days after the ratification. Therefore, the enter-into-force time is likely in February 2022 for South Korea.

Review of the Highlights of the RCEP

The RCEP is anticipated to further integrate intra-Asian economic activities. It will gradually remove 90% of the tariffs among the member states in the next ten to fifteen years. According to the assessment by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the RCEP would be likely to add 245 billion USD annually to the region’s income by 2030, under the assumption that the implementation remains on track [1] and it also estimates that it would be Japanese, South Korean, and Chinese exports that will benefit most from the agreement, with 11.2%, 6%, 4.7% growth rates respectively by 2030.

- China-Japan-South Korea Trilateral Free Trade

Upon the RCEP entering into force in Korea in the first quarter of 2022, a free trade agreement will be effectively implemented between China, Japan, and Korea. Under the RCEP, South Korea and Japan will gradually eliminate 83% of the tariffs on each other's products. China will also remove 86% of the tariffs on Japanese goods entering the Chinese market. One highlight is the gradual removal of tariffs on the automotive industry, though 20%-25% of Chinese tariffs will still be in place for Korean and Japanese autos.

- Harmonized Rules of Origin among signatories

For RCEP member states, products with a minimum of 40% components sourced within the RCEP countries, a relatively low threshold, will be treated as locally manufactured [2]. There will be a harmonized certificate of origins that will be used among the member states. As such, the harmonized Rules of Origin is anticipated to significantly reduce the administrative burden for intra-regional trade.

- Facilitate E-commerce Activity

One chapter in the RCEP is dedicated to E-commerce, including free cross-border transfer of information by electronic means for e-commerce activity and the reiteration of not imposing customs duty on electronic transmissions between parties. This chapter will particularly benefit Chinese cross-border e-commerce activities due to its gigantic e-commerce industry and its strategic interest in expanding in Southeast Asia.

This raises a key question: what impact will a more integrated Asian economy have on an increasingly fragmented global supply chain? Here we attempt to identify some possible answers based on intra-Asian trade statistics for 2021, which show some signs of integration.

Regional Economic Integration during the Pandemic

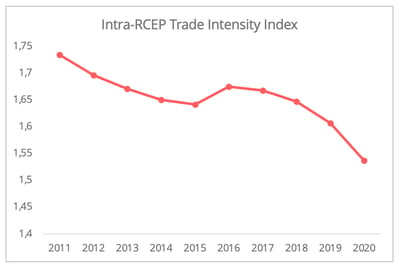

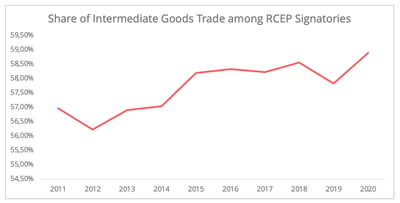

Overall, in the past decade, the economic integration among the RCEP signatories has shown limited progress in comparison to their trade with the world (Figure 1). From 2011 to 2020, the trade volume among RCEP member states increased by 6% [3], whereas the RCEP signatories’ total trade with the world has grown by 7%.

Figure 1- Data Source: OECD Bilateral Trade in Goods by Industry and End-use Category Data and WTO Data, Author’s calculation [4]

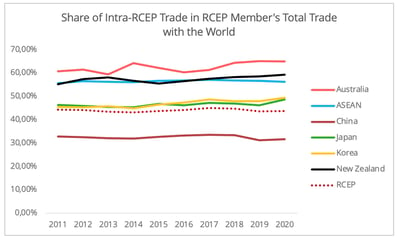

Furthermore, the slight drop of the share of intra-regional trade in the total world trade may connote a stalemate in regional trade integration (Figure 2) in the past decade.

Figure 2 - Data Source: OECD Bilateral Trade in Goods by Industry and End-use Category Data

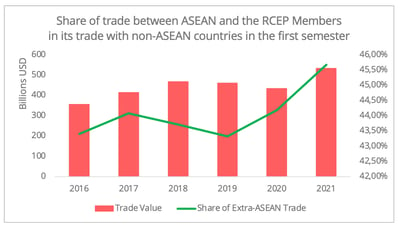

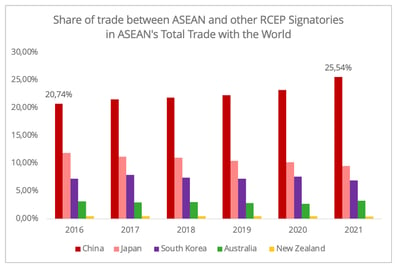

However, during the pandemic a deepening of economic ties between ASEAN and its Asian counterparts is discernible. The share of trade between ASEAN and its RCEP counterparts in the first semester of 2021 has increased to 46% from 43% in pre-covid 2019, this is mainly attributed to these tightened economic ties between China and ASEAN (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Data Source: ASEAN Statistics

The trade between China and ASEAN accounts for around a quarter of ASEAN's total world trade with external members, up from one fifth in 2016 (Figure 4). On the other hand, the fall in ASEAN's trade with Japan and Korea accounts for the decreasing share in ASEAN's total trade with external members.

Figure 4 - Data Source: ASEAN Statistics

Asia in the Reconfigured Global Supply Chain

The global pandemic has prompted companies to re-examine their supply chain strategy. The desire to shorten supply chains has become more salient in 2021, amidst the logistical upheaval. Let's look at the potential impacts of this trend.

- In Asia for Asia

Overall, a more integrated intra-Asian economy aligns with this current evolution of the supply chain.

In the Asia-Europe connection, the RCEP could be an impetus for European companies to invest in the member states of this partnership agreement to form a regional supply chain, and benefit from the lowered tariffs and harmonized rule of origins, therefore expanding their presence in the Asian market. This could be particularly attractive, considering the EU already has free trade agreements with multiple RCEP member states, such as Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and Singapore. European companies have already implemented a strategy of locating their activities in China with a view to producing "in China for China", which has been further accentuated by the pandemic. The more integrated Asian economy and the expansion of the Asian market could extend this concept to "in Asia for Asia". An example of this is Porsche's latest investment in the construction of a manufacturing site in Malaysia targeting the Southeast Asian market.

- Evolution of the role of global export hubs

The fragmentation of the global supply chain could also curb the heavily export-oriented Asian economy. The textile industry is among the early birds showing signs of nearshoring. According to the latest survey from McKinsey, 71% of apparel and fashion companies are planning to increase their nearshoring share by 2025. The main arguments put forward are logistical aspects, in particular high transport costs, and the desire to reduce their carbon footprint.

Of course, nearshoring and reshoring do not take place overnight. Despite the EU and the US aiming to bring some strategic sectors back home, Asia remains the export powerhouse for some of these strategic industries, such as the semiconductor sector and electric vehicle batteries. According to the WTO, in the first semester of 2021, one third of the top 15 intermediate goods exporters were RCEP signatories.

Let us take China’s surge in exports of electric vehicles (EV) in 2021 as an example. From January to November 2021, China exported 291,000 units worldwide, with a 436.5% YoY growth rate [5], 75% of which were to the European market [6]. The surge can be attributed mainly to Tesla’s strategy of making its Shanghai Gigafactory an export hub, a strategy also being adopted by other auto manufacturers. In the long term, the reshoring effort of the European and US companies in EV manufacturing will reduce reliance on China for their domestic markets. However, given its well-established expertise in this industry, China will continue to serve as a hub for electric vehicle manufacturers to export to other regions, where technical know-how is less established.

The two aforementioned trends could jointly promote the trade of intermediate goods among RCEP members, where only a modest increase has been observed in the past decade (Figure 5). In addition, the relatively low threshold for the Rules of Origin under the RCEP may also foster an increase of intermediate goods imports from outside of the region.

Figure 5 - Data Source: OECD Bilateral Trade in Goods by Industry and End-use Category Data.

The impact on the logistics sector

As the backbone of trade activities, the logistics industry also responds to their trends. The surging intra-Asian demand motivates service providers to offer more dedicated services. The booming e-commerce and retail contribute to the soaring demand. This demand is expected to continue to grow, as the RCEP is anticipated to boost the regional cross-border e-commerce activity.

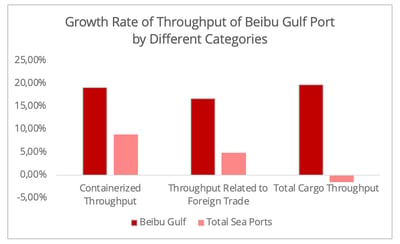

Apart from ocean freight, the development of the international land-sea trade corridor between China and ASEAN is also worth noting. As one of China’s flagship international infrastructure projects, this multimodal route (rail-sea connection) shipped 360 thousand TEUs in the first eight months of 2021, a 265% growth rate in comparison to the same period last year. The throughput of Beibu Gulf Port, the gateway to this network, has significantly outperformed the overall throughput of Chinese seaports with the highest growth rate among the top 10 seaports in China (Figure 6). The newly finished China-Laos railway connection will be likely to bring more multimodal shipping possibilities connecting China and ASEAN, allowing for competitive road-rail services compared to air freight, and will link Southwest China with Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore.

Figure 6 - Data Source: Chinese Ministry of Transport

As for inter-regional shipping, reshoring and nearshoring will undoubtedly affect shipping demand. According to a simulation study conducted by the ADB, under a hypothetic scenario of 5% reshoring, Asia’s exports by air transport would be the most affected, and water transport will be hit the hardest in Asian imports [7]. However, with Asia becoming an export hub for some emerging industries, this would create new demand. For instance, China's ambition to champion the EV industry could generate more flow for Ro/Ro shipping, especially to the European market.

Overall, the newly implemented RCEP is expected to accelerate intra-Asian connectivity. As the world's manufacturing hub, a more integrated Asian economy also brings new dynamics to the global supply chain. Our analysis is based on the assumption of a well-implemented RCEP. However, it should be kept in mind that intra-Asian trade has always been deeply entangled with the regional political climate. For instance, the tension between China and Australia is currently disrupting economic activity between the two countries. So, we should be cautiously optimistic about what 2022 will bring us.

[1] The data here is based on the assumptions that all signatories ratified the agreement, and the implementation is on track.

[2] This rule will be implemented in the ratified countries only.

[3] This is based on the OECD Bilateral Trade in Goods by Industry and End-use Category Data.

[4] The intra-regional trade intensity index, based on the definition from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) is the “ratio of intra-regional trade share to the share of world trade with the region” and an intra-RCEP trade intensity index as calculated herein is based on the method described by ADB. An index greater than 1 “indicates that trade flow within the region is larger than expected given the importance of the region in world trade”. For details please see: https://aric.adb.org/integrationindicators/technotes#intra-regional-trade-share.

[5] The data is generated from the monthly report of China Association of Automobile Manufacturers.

[6] Here includes the EU, the EEA countries, and the UK.

[7] The information is extracted from the explanations and the graphs in the presentation given by ADB researchers. For details, please check Global value chain reshoring: Impact and policy responses, Asian Development Bank.

Ganyi Zhang

PhD in Political Science

Our latest articles

-

4 min 04/03/2026Lire l'article

-

Heavy goods vehicle registration figures for 2025

Lire l'article -

Subscriber France: Road transport prices remained almost stable in January

Lire l'article